The Short Call Option Playbook for Income and Risk

If a stock moves past your strike, the option can be assigned — meaning you'll have to sell (in a call) or buy (in a put). Knowing the assignment probability ahead of time is key to managing risk.

Posted by

Related reading

A Step-by-Step Covered Calls Example for Consistent Income

Unlock consistent income with our step-by-step covered calls example. This guide breaks down the strategy, risks, and outcomes to help you trade confidently.

Long Call and Short Put The Ultimate Synthetic Stock Guide

Unlock the power of the long call and short put strategy. This guide explains how synthetic long stock works, its benefits, risks, and how to execute it.

What is a Call Spread? A Clear Guide to Bull and Bear Spreads

What is a call spread? Discover how bull and bear spreads limit risk and sharpen your options trading strategy.

When you sell a short call option, you're selling a contract that gives someone else the right to buy 100 shares of a stock from you at a set price. For taking on this obligation, you get paid an immediate cash premium. It’s a strategy built on the belief that a stock's price will either stay put or drift downward.

Decoding the Short Call Option

Think of it like this: you own a house valued at $500,000, and you don't expect its value to jump anytime soon. A potential buyer pays you $5,000 today for the option to buy your house for $525,000 anytime in the next 60 days. You pocket the $5,000 immediately.

If the housing market stays flat or drops, their option expires worthless. You keep the $5,000 and your house, free and clear. You just successfully "sold a call." If the value skyrockets to $550,000, they’ll likely buy your house for $525,000, and you'll have to sell. You still keep the $5,000 premium, but you miss out on the extra upside.

As the seller (often called the "writer"), your ideal outcome is for the option to expire worthless. This happens if the stock price never rises above the agreed-upon sale price. When it does, you simply keep the premium you were paid upfront as pure profit. It’s a go-to strategy for investors with a neutral-to-bearish view on a stock.

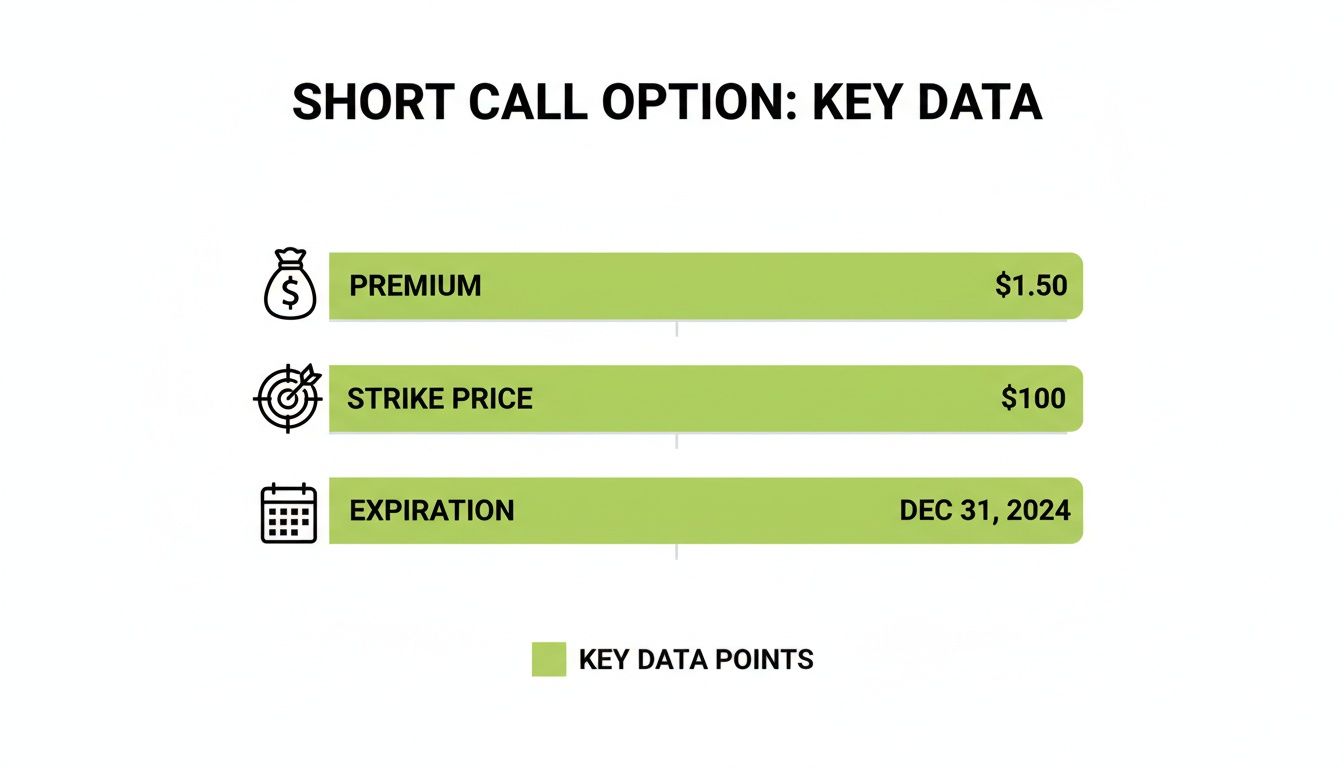

The Core Components

Every short call trade is defined by three key pieces. Getting these straight is crucial to understanding the mechanics.

- Premium: This is the cash you get paid right away for selling the contract. It’s your maximum possible profit, and it's yours to keep no matter what happens.

- Strike Price: This is the locked-in price where you are obligated to sell your 100 shares if the buyer decides to exercise their option.

- Expiration Date: This is the final day of the contract. If the stock is trading below the strike price at expiration, the contract dies, and your obligation to sell vanishes.

The interplay between these three elements shapes the entire trade. A short call is a fantastic way to generate income, but it comes with what's known as asymmetric risk. Your potential gain is capped at the premium you collect, while your potential loss is theoretically unlimited if the stock soars unexpectedly.

Historically, sellers of out-of-the-money short calls with about 30 days until expiration might collect premiums between 1% to 6% of the stock's value. But when markets get volatile—think the 2008 financial crisis or the March 2020 crash—those premiums can spike, creating massive paper losses for sellers caught on the wrong side of a rally. For deeper historical data, platforms like OptionMetrics offer comprehensive datasets.

A short call option is really just a bet that a stock won't hit a certain price by a certain date. You are selling time and probability to another trader in exchange for immediate cash.

Let's quickly recap the key details of selling a call option from the seller's perspective.

Short Call Option At a Glance

| Component | Description for the Seller (Writer) |

|---|---|

| Goal | For the option to expire worthless, allowing you to keep the full premium. |

| Max Profit | Capped at the initial premium received when selling the contract. |

| Max Risk | Theoretically unlimited if the stock price rises indefinitely (for naked calls). |

| Market Outlook | Neutral to Bearish. You don't expect the stock to rise above the strike price. |

| Breakeven Point | Strike Price + Premium Received Per Share. |

| Ideal Outcome | The stock price closes below the strike price at expiration. |

Understanding these components is the first step toward using short calls effectively to generate consistent income from your portfolio.

Decoding the Payoff and Risk Profile

At its heart, selling a short call is a trade-off: you get paid a small amount of cash today in exchange for taking on a future obligation. Nailing down this payoff structure is the first step to understanding what you stand to gain and, more importantly, what you’re putting on the line.

Your absolute best-case scenario is simple: you collect the premium, and it becomes pure profit. This happens when the stock price stays below your chosen strike price, causing the option to expire worthless. You keep the cash, no strings attached. It's this clear, defined profit that makes selling calls so appealing for generating income.

But the other side of that coin is where things get interesting—and potentially dangerous.

The Asymmetric Risk of a Short Call

While your profit is capped at the premium you received, your potential loss is, in theory, unlimited. This is the scary part. If the stock price rockets past your strike price, your losses start piling up. Since a stock can technically go up forever, so can your losses.

This creates what’s known as an asymmetric risk profile: a small, known potential gain versus a large, undefined potential loss. Grasping this concept is the single most important thing you need to do before ever selling a call option.

Your entire trade boils down to three key pieces of the puzzle: the premium you collect, the strike price you choose, and the expiration date.

These three variables work together to determine where you make money, where you break even, and where you start to feel the pain.

Calculating Your Breakeven Point

Your breakeven point is the exact stock price where you're flat at expiration—no profit, no loss. It's the line in the sand for your trade. Thankfully, the math is straightforward.

Breakeven Point = Strike Price + Premium Received Per Share

If the stock is below this price at expiration, you’re in the green. If it’s above this price, you’re in the red. The higher it goes past your breakeven, the deeper your loss.

Let's make this real with an example.

- Stock: XYZ, currently trading at $48 per share.

- Your Outlook: You're neutral to slightly bearish. You don't see it breaking above $50 in the next month.

- Your Action: You sell one short call option with a $50 strike price that expires in 30 days.

- Premium Received: You pocket $2.00 per share, which comes out to $200 for the contract (since one contract represents 100 shares).

Now, let's find that breakeven point:

$50 (Strike Price) + $2.00 (Premium) = $52 Breakeven Price

This means XYZ has to climb all the way past $52 per share before you actually start losing money on the trade. For a deeper dive into these numbers, check out our guide on how to calculate call option profit.

"With a short call, you accept a known, limited reward in exchange for an unknown, unlimited risk. The premium is compensation for accepting that risk. Never forget which side of that equation holds more power."

Let's see how a few different closing prices would affect your bottom line:

- Scenario 1: Stock closes at $49. The option is worthless since it's below the $50 strike. You keep the full $200 premium as your profit. Easy money.

- Scenario 2: Stock closes at $52. The stock is above the strike, but you’re sitting right at your breakeven. The $200 premium you collected is perfectly cancelled out by the $200 paper loss on the shares ($52 market price - $50 strike price = $2 loss per share). Your net result is $0.

- Scenario 3: Stock closes at $55. The stock has rallied hard against you. Your loss is the difference between the market price and your breakeven: $55 - $52 = $3 per share. That's a total loss of $300.

This simple example lays bare the core risk of the strategy. A small move in your favor delivers your maximum profit, but a big move against you can wipe out that premium and then some.

Covered vs Naked Short Call Strategies

When you sell a call option, you face a crucial choice that completely changes the game. It’s the difference between building a fence around your property and walking a tightrope without a net. These two paths are known as covered calls and naked calls.

Understanding which one fits your portfolio and stomach for risk is non-negotiable. While both strategies involve selling a call and collecting a premium, their mechanics and potential outcomes couldn't be more different. One is a conservative income tool; the other is a high-stakes bet reserved for the most seasoned traders.

The Covered Call: A Conservative Income Play

Selling a covered call is the most common and recommended way for investors to start selling options. The strategy is called "covered" because you already own the underlying shares you might have to sell. For every call contract you sell, you need to own at least 100 shares of that stock.

Think of it like renting out a spare room in a house you already own. You collect rent (the premium) from a tenant (the option buyer), but your obligation is covered because you have the asset—the house itself. If the buyer decides to exercise their option, you just hand over the shares you were already holding.

This approach is incredibly popular for a few reasons:

- Income Generation: It’s a great way to earn a steady income from stocks you were planning to hold for the long haul anyway.

- Defined Risk: The risk isn't financial loss in the traditional sense. Instead, your risk is the opportunity cost of missing out on huge gains if the stock skyrockets past your strike price.

- Lower Margin: Since you own the shares, brokers don’t demand a ton of extra collateral, making it accessible for most investors.

The covered call is a foundational strategy for turning a static stock portfolio into an active income stream. For a much deeper dive, check out our comprehensive covered call strategy for income guide.

The Naked Call: A High-Stakes Wager

Now for the other side of the coin: the naked call. It's also known as an "uncovered call," and for a chillingly simple reason—you don't own the underlying 100 shares. You're selling a promise to deliver shares you don't have, betting heavily that you’ll never be asked to make good on it.

If a covered call is like renting out a room you own, a naked call is like selling a front-row ticket to a sold-out concert that you don't actually possess, hoping you can buy one cheap from a scalper if the buyer shows up. If ticket prices explode, you’re forced to buy at an insane price to fulfill your promise, leading to massive, potentially catastrophic losses.

A naked short call option exposes the seller to theoretically infinite risk. Since there is no limit to how high a stock's price can climb, there is no limit to how much money a naked call seller can lose.

This strategy is strictly for advanced traders with a very high-risk tolerance, a deep understanding of the market, and a lot of capital. Brokers have strict requirements just to allow these trades, often demanding huge account balances and proven experience. The profit is still capped at the premium you collect, but the potential loss is boundless.

Head-to-Head Comparison

The choice between selling a covered or naked call boils down to what assets you have, what your goals are, and how much risk you can handle. Let's put them side-by-side to make the differences crystal clear.

Covered Call vs. Naked Call Comparison

This table offers a direct comparison, highlighting the fundamental distinctions that every options seller needs to understand.

| Feature | Covered Call | Naked Call |

|---|---|---|

| Underlying Shares | You own 100 shares for each contract sold. | You do not own the underlying shares. |

| Primary Goal | To generate income on an existing stock holding. | To profit from a strong belief that a stock's price will fall or stagnate. |

| Maximum Profit | Capped at the premium received. | Capped at the premium received. |

| Maximum Risk | Opportunity cost of missing stock gains above the strike price. | Theoretically unlimited financial loss. |

| Capital Required | Cost of owning 100 shares of the stock. | Significant margin is required by the broker as collateral. |

| Ideal Investor | Long-term investors, income-focused traders, beginners. | Highly experienced, speculative traders with high-risk tolerance. |

Ultimately, covered calls are a strategic way to generate income from assets you already own, making them a cornerstone for many investors. Naked calls, on the other hand, are a pure bet on a stock's direction and should only be considered by those who fully grasp—and can afford—the unlimited risk involved.

Short Call Trading in the Real World

Theory is great, but seeing how a short call option actually behaves out in the wild is where the real learning happens. Let's step away from the clean lines of payoff diagrams and dive into two very different, real-world scenarios.

These examples show how the same tool can be used for completely different goals—one trader looking for conservative income, the other making a high-stakes bet on a volatile stock.

Scenario 1: The Covered Call for Steady Income

First up is Sarah, a long-term investor. She owns 200 shares of a stable, dividend-paying company we'll call Blue Chip Inc. (BCI). The stock is trading at $148, and while she’s happy to hold on, she wants to squeeze a little extra cash flow out of her position. In her view, BCI isn’t likely to shoot to the moon in the next month.

This situation makes her a perfect candidate for a covered call.

- Her Position: Owns 200 shares of BCI.

- Her Action: Sarah sells two covered call contracts on BCI.

- Trade Details:

- Strike Price: $155 (comfortably above the current price)

- Expiration Date: 30 days out

- Premium: $1.75 per share

By selling those two contracts, Sarah immediately pockets $350 ($1.75 x 100 shares x 2 contracts). That cash lands in her account right away, and it’s hers to keep, no matter what happens next.

Outcome A: BCI Stays Below the Strike Price

Fast forward 30 days, and BCI is trading at $152. Because the stock price is below her $155 strike, the options expire worthless. Why would the buyer pay $155 for shares they can get for $152 on the open market? They wouldn't.

This is a clear win for Sarah. Her obligation to sell simply vanishes. She keeps her 200 shares of BCI, and the $350 premium is pure profit. She successfully generated income from an asset she already owned.

Outcome B: BCI Rallies and Gets Called Away

Now, let’s imagine BCI got some unexpected good news and the stock rallied hard. At expiration, it's trading at $158 a share. Since the stock price blew past the $155 strike, the option buyer exercises their right.

Sarah is now obligated to sell her 200 shares at the agreed-upon $155 price. Her shares are "called away." Sure, she missed out on the gains between $155 and $158, but she still sold her shares for a nice profit over her cost basis and keeps the $350 premium. Not a bad outcome at all.

Scenario 2: The Naked Call Speculation

Next, meet Mark. He’s an experienced trader who isn’t afraid of risk. He's been watching a hyped-up tech stock, Innovate Corp (INNO), which has rocketed from $80 to $120 in just a few weeks. Mark is convinced the rally is overdone and a pullback is coming. He doesn't own a single share of INNO.

He decides to sell a naked call to bet on his bearish theory.

- His Position: No shares of INNO.

- His Action: Mark sells one naked call contract on INNO.

- Trade Details:

- Strike Price: $125

- Expiration Date: 21 days out

- Premium: $4.00 per share

Mark collects a $400 premium. His bet is simple: INNO will stay below $125 for the next three weeks. His breakeven price on the trade is $129 (the $125 strike plus the $4 premium).

Selling a naked call is one of the riskiest strategies in options trading. It's a pure bet against a stock's upward momentum, and a wrong prediction can lead to financially devastating, unlimited losses.

Outcome A: The Stock Pulls Back as Expected

Just as Mark predicted, the hype around INNO fizzles out. At expiration, the stock has dropped to $115. The $125 call option he sold expires completely worthless.

The result? He walks away with his maximum possible profit: the entire $400 premium. For him, the high risk paid off handsomely.

Outcome B: A Catastrophic Short Squeeze

In an alternate reality, a major tech firm announces an unexpected acquisition of INNO. The stock doesn't just pull back—it explodes. The share price skyrockets to $170 by expiration.

Mark is now in a disastrous position. The option is deep in-the-money, and he gets assigned. He is now on the hook to deliver 100 shares of INNO at $125. Since he owns none, his broker steps in, forcing him to buy 100 shares at the market price of $170 and immediately sell them for $125.

The math is brutal:

($170 Market Price - $125 Strike Price) x 100 shares = a $4,500 loss.

Even after you factor in the $400 premium he initially collected, Mark's net loss is a painful $4,100. This single trade is a stark reminder of the immense danger of naked calls, where one piece of bad luck can cause losses that dwarf any potential gain.

How to Manage Trades and Avoid Assignment

Selling a short call feels easy when the stock price cooperates, either staying flat or drifting down. You just sit back, let the contract expire worthless, and pocket the full premium. But what happens when the trade moves against you? When the stock starts climbing toward your strike price, that's when you need a game plan.

This is where proactive management makes all the difference. Your main objective is to avoid assignment — the point where the buyer exercises their right and forces you to sell 100 shares at the strike price. This usually happens when the option is in-the-money as expiration gets close.

The good news is you don’t have to just watch it happen. You have defensive moves to make. The two most common are either buying back the option to close your position or rolling it to a future date. Both put control back in your hands.

Buying to Close Your Short Call

The simplest way out of a losing trade is to buy to close the option. Think of it as hitting the eject button. You originally sold to open the position, so to get out, you do the exact opposite: you buy that same contract back from the market.

This instantly cancels your obligation to sell the shares. The trade is over, and you're no longer on the hook.

Most sellers do this when the loss hits a pre-determined limit. For example, if you collected a $200 premium, you might set a rule to buy the option back if its price doubles to $400. You’d lock in a $200 loss, which is never fun, but it's far better than letting a naked call run wild, where losses can be unlimited.

The Art of Rolling the Position

A more advanced tactic is rolling the option. This is a single, two-part transaction where you simultaneously buy to close your current short call and sell to open a new one. The new option will have a later expiration date, a higher strike price, or both.

Rolling is all about giving your trade more time to work out or improving your position. There are three ways to do it:

- Rolling Out: Close your current option and open a new one with the same strike but a later expiration. This gives the stock more time to hopefully pull back.

- Rolling Up: Close your current option and open a new one with the same expiration but a higher strike price. This gives the stock more room to climb before you’re at risk again.

- Rolling Up and Out: This is the classic defensive move. You move to a higher strike price and a later expiration, giving yourself more room and more time.

The goal when rolling is usually to collect a net credit. That means the cash you get from selling the new option is more than what it costs to buy back your old one. This effectively lowers your breakeven point and keeps you in the game without adding more of your own money.

For instance, if your $50 strike call is getting challenged, you could roll it to a $55 strike that expires next month. This one strategic move can turn what looked like a sure loser into a potential winner. It’s an essential skill for any serious option seller, and you can learn the finer points in our guide to rolling over options in our guide.

Your Questions Answered: Short Calls in the Real World

Even when you've got the mechanics down, plenty of questions pop up when it comes to actually selling calls. Let's tackle some of the most common ones to clear up any lingering doubts and help you trade with more confidence.

We'll cover when to pull the trigger, what happens when a trade goes against you, and how to pick the right strike price to find that sweet spot between risk and reward.

When Is the Best Time to Sell a Short Call?

The ideal moment to sell a short call is when you're neutral to bearish on a stock. In plain English, you believe the stock will either trade sideways, drift down, or maybe inch up a little—but you're betting it won't surge past your strike price before the option expires. It’s a bet against a big breakout.

On top of that, savvy sellers love hunting for periods of high implied volatility (IV). High IV pumps up option premiums, meaning you get paid more for taking on the exact same risk. Think of it as selling insurance right before a storm is forecast; the price goes way up. That extra premium gives you a much bigger cushion if the stock moves against you.

What Happens If My Short Call Expires In-The-Money?

If the stock price is above your strike price at expiration, your short call is in-the-money (ITM), and you should expect to be assigned. Assignment is just the fancy term for having to make good on your end of the deal.

- For a covered call: This is pretty straightforward. You'll sell the 100 shares you already own at the strike price. Your shares get "called away," and you keep the premium you collected.

- For a naked call: This is where the pain starts. You're forced to buy 100 shares at the high current market price, only to immediately sell them at the lower strike price. This almost always results in a substantial loss.

To avoid this outcome, traders don't just sit and wait. They actively manage the position by either buying the option back to close it (often for a loss) or rolling it to a later expiration date, giving the trade more time to work out.

Can I Lose More Than the Margin for a Naked Call?

Yes, absolutely. This is the single most important risk to understand with naked calls. The margin your broker holds is just a security deposit; it is not your maximum possible loss.

Since a stock's price can technically rise forever, the potential loss on a naked short call is also theoretically unlimited. A surprise buyout, a positive earnings shock, or any sudden news can cause a stock to rocket upward, leading to losses that could demolish your account and go far beyond your initial margin.

This is exactly why brokers have such strict requirements for selling naked options. It's a strategy reserved for experienced traders who have a deep respect for its unlimited risk.

How Do I Choose the Right Strike Price?

Picking a strike price is all about a trade-off between income and safety. The right choice comes down to your personal risk tolerance and how you see the stock behaving.

A strike price closer to the stock's current price will always have a bigger premium. Why? Because there's a higher chance it will finish in-the-money, so you're getting paid more for taking on that extra risk.

On the other hand, a strike price that's far away from the current price will have a smaller premium but a much higher probability of expiring worthless. For an option seller, that's the goal. It's the safer, but less profitable, choice.

Many traders lean on data to make this call. A great tool for this is Delta, which gives a rough estimate of the probability an option will expire in-the-money. A common rule of thumb is to sell calls with a Delta of 0.30 or less, which translates to a 70% or higher probability that the option will expire worthless. This data-driven approach takes the emotion out of the decision and helps you systematically find your perfect balance.

Making these probability-based decisions can be complex, but you don't have to do it alone. Strike Price provides real-time probability metrics for every strike price, empowering you to find the perfect balance between premium income and safety. Our platform sends smart alerts for high-reward opportunities and early risk warnings, turning guesswork into informed action. Start making data-driven trades today by visiting https://strikeprice.app.