Your Guide to Taxes on Covered Calls

If a stock moves past your strike, the option can be assigned — meaning you'll have to sell (in a call) or buy (in a put). Knowing the assignment probability ahead of time is key to managing risk.

Posted by

Related reading

A Trader's Guide to Extrinsic Value Option Profits

Unlock the power of the extrinsic value option. Learn what drives it, how to calculate it, and strategies to profit from time decay and volatility.

A Trader's Guide to the Poor Man Covered Call

Discover the poor man covered call, a capital-efficient options strategy for generating income. Learn how to set it up, manage it, and avoid common mistakes.

A Trader's Guide to Shorting a Put Option

Discover the strategy of shorting a put option. Our guide explains the mechanics, risks, and rewards of cash-secured vs. naked puts with clear examples.

When you sell a covered call, the premium you collect is generally taxed as a short-term capital gain in the year the option expires or you close the position. If your shares get assigned, that premium gets rolled into your final sale price, and the total gain is then taxed based on how long you held the stock.

How Covered Call Taxes Actually Work

Thinking about taxes on covered calls can feel like a headache waiting to happen, but the concept is simpler than it seems. The key thing to remember is that the IRS doesn't care about the premium you collected until the option's story is over. The tax event isn't triggered when the cash hits your account, but when the contract is officially resolved.

A covered call trade can end in one of three ways, and each has a different tax outcome:

- The Option Expires Worthless: The buyer doesn't exercise their right. You keep your shares and the entire premium.

- The Stock is Assigned (Called Away): The stock's price shoots past your strike, the buyer exercises the option, and you're forced to sell your shares at the agreed-upon price.

- You Close the Position Early: You buy back the same call option you sold, usually to lock in a profit or cut your losses before expiration.

Knowing which path your trade takes is the first step to getting the taxes right. Each outcome leads to a specific taxable event with its own set of rules.

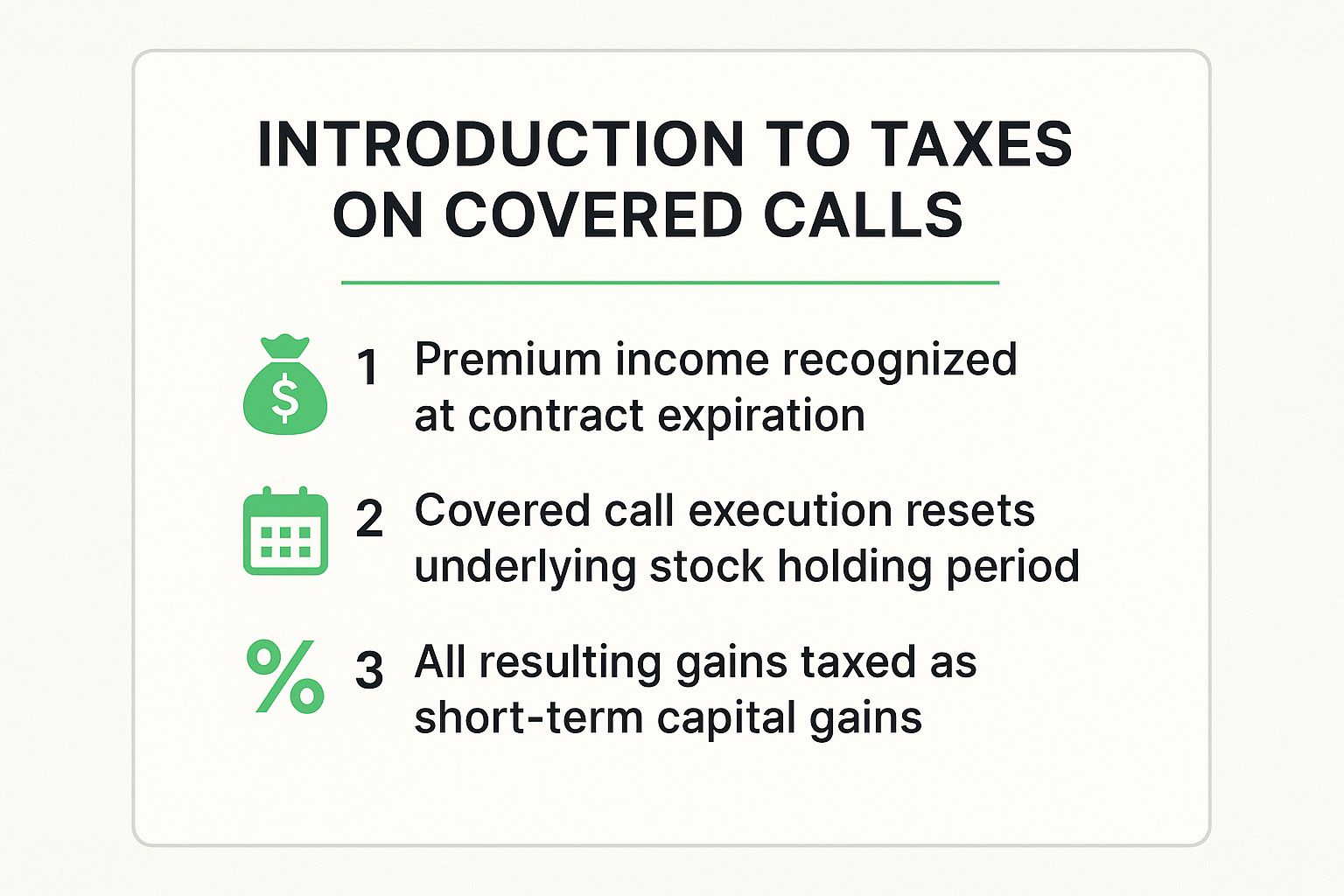

The infographic below breaks down the core tax principles you'll want to keep in mind for your covered call strategy.

As the visual highlights, the premium income isn't recognized for tax purposes until the contract ends. Also, an assignment can mess with your stock's holding period—both are critical details for smart tax planning.

Covered Call Tax Scenarios at a Glance

To make it even clearer, here's a quick cheat sheet. This table summarizes the tax treatment for the three main outcomes of a covered call position, giving you a quick reference for each potential result.

| Scenario | Premium Tax Treatment | Impact on Holding Period |

|---|---|---|

| Option Expires Worthless | Taxed as a short-term capital gain in the year of expiration. | No impact. The holding period for your stock continues uninterrupted. |

| Stock is Assigned | The premium is added to the sale price, reducing your cost basis. The total gain is then taxed based on the stock's original holding period (short-term or long-term). | The holding period for the stock ends on the date of assignment. |

| You Close the Position | The net profit or loss (premium received minus cost to close) is taxed as a short-term capital gain or loss. | No impact. Your stock's holding period continues as if the option was never sold. |

This table should help you quickly see how each scenario plays out from a tax perspective. Keeping these rules in mind will help you avoid any surprises when it's time to file.

The Tax Treatment of Covered Call Premiums

When you sell a covered call, the premium hits your brokerage account almost right away. This immediate cash is a huge part of the strategy's appeal, but it's also where the tax confusion starts. Here’s the number one rule to remember: that premium is not taxed the moment you receive it.

Think of it like a security deposit on a rental. You have the cash, but its final purpose isn't decided until the lease—the option contract—is over. The IRS only cares about the premium once the option expires, gets assigned, or you buy it back to close the position.

This "wait and see" approach is a core concept. The cash you collect isn't considered income just yet. It's in a holding pattern until the trade is fully resolved.

When the Call Expires Worthless

The best-case scenario for most covered call sellers is seeing the option expire worthless. This happens when the stock price fails to climb above your strike price, leaving the buyer with no reason to exercise their right to purchase the shares.

In this clean outcome, the tax treatment is simple but often trips up new traders.

The entire premium you collected becomes a short-term capital gain. It doesn't matter if you've owned the underlying stock for five years; the income from that expired 30-day call is taxed as a short-term gain in the year the option expires.

Key Takeaway: Premiums from expired calls are always short-term capital gains. This means they get taxed at your ordinary income rate, which is almost always higher than the long-term capital gains rate.

This is a critical detail for tax planning. Many people mistakenly lump these gains in with their long-term profits, only to get a nasty surprise from the IRS. For a complete breakdown, check out our full guide on covered call tax treatment.

Understanding Qualified Covered Calls

The IRS knows that clever investors can use options to play games with their taxes. To keep things fair, they created rules around what’s known as a “qualified covered call.” Sticking to these rules helps you avoid tax headaches like the dreaded straddle rule.

A qualified covered call needs to meet a couple of basic conditions:

- It must have more than 30 days left until expiration when you first sell it.

- The strike price can’t be “deep in the money,” which would make getting assigned a near certainty.

Writing qualified covered calls is simply good practice. It keeps your stock's holding period from being paused and makes your tax reporting much simpler, steering you clear of complex anti-abuse rules.

What Happens When Your Stock Gets Assigned at Tax Time?

While many traders hope their covered calls expire worthless, assignment is a perfectly normal—and often profitable—part of the game. It happens when the stock price climbs above your strike price, and the option buyer decides to exercise their right to buy your shares.

When your stock gets "called away," it triggers a taxable event. The way you calculate this is a little different from a simple expired call.

The first thing you need to do is figure out your actual sale price. This isn't just the strike price. It's the strike price plus the premium you originally pocketed for selling the option. Think of that premium as a sweet little bonus on top of your stock sale.

This adjusted sale price is the number that matters for calculating your capital gain or loss. Honestly, getting this part right is one of the most important things to master for taxes on covered calls.

Calculating Your Capital Gain (or Loss)

Once you've got that adjusted sale price, the math is pretty simple. You just subtract what you originally paid for the shares (your cost basis) from this new sale price. The number you get is your total capital gain or loss for the whole trade.

Let’s walk through a quick example. Say you bought 100 shares of a stock at $45 and sold a covered call with a $50 strike, collecting a $200 premium. If the stock gets assigned, here’s how the numbers break down:

- Adjusted Sale Price: ($50 Strike Price x 100 shares) + $200 Premium = $5,200

- Original Cost Basis: $45 x 100 shares = $4,500

- Total Capital Gain: $5,200 - $4,500 = $700

That $700 gain is what you'll need to report. But the next question is the one that really impacts your tax bill: is it a short-term or long-term gain?

The Stock's Holding Period Is the Deciding Factor

The type of capital gain you have—and the tax rate you'll pay—boils down to one thing: how long you held the underlying stock, not the option. This is where good record-keeping really pays off.

The difference between short-term and long-term gains is the single most important factor when your shares are assigned. A long-term gain gets taxed at a much lower rate, which could save you hundreds or even thousands of dollars.

If you held the stock for one year or less before it was called away, your entire gain is considered a short-term capital gain. This gets taxed at your ordinary income tax rate, which is your highest rate. Ouch.

But if you held the stock for more than one year, the profit qualifies as a long-term capital gain, which comes with much friendlier tax rates.

For instance, if you sold 100 shares at a $55 strike after getting a $200 premium, your total proceeds are $5,700. If you originally paid $5,000 for those shares and held them for over a year, that $700 profit is a long-term gain. You can find more details on how holding periods affect covered call tax outcomes in this helpful breakdown from VectorVest.

So far, we’ve walked through what happens when your calls expire worthless or when your shares get called away. But there’s a third, incredibly common scenario every trader needs to get comfortable with: actively buying back your option to close the position.

This isn't a sign of failure. Far from it. Closing a trade early is a strategic move, often used to lock in a quick profit on the option premium or to smartly cut ties with a trade that’s starting to feel a little shaky.

When you buy back the same call you sold, you're creating a completely separate taxable event. Think of it as its own mini-trade, totally independent of what happens with your underlying stock. Its tax treatment stands on its own.

The outcome is simple: you’ll end up with either a capital gain or a capital loss on the option itself.

The Basic Math

Figuring out your gain or loss is refreshingly straightforward. You just look at the premium you collected when you sold the call and compare it to the price you paid to buy it back.

- If you buy it back for less than you sold it for, you’ve pocketed a capital gain.

- If you buy it back for more than you sold it for, you’ve realized a capital loss.

Let’s say you sold a call and collected a $200 premium. A few weeks go by, the option's value decays, and you snag it back for just $50. Boom. You’ve just locked in a $150 capital gain ($200 - $50). Easy peasy.

Key Takeaway: Buying to close your option has zero effect on your stock's holding period. The clock on your shares keeps right on ticking, preserving your journey toward a potential long-term capital gain on the stock itself.

Is It Short-Term or Long-Term?

This is where things get interesting. When your shares are assigned, the tax outcome is tied to the holding period of your stock. But when you close the option early, the IRS only cares about the holding period of the option contract itself.

It's a crucial distinction.

Since the vast majority of covered calls are written with expirations just weeks or months away, any gain or loss you realize from closing the position will almost always be short-term.

- Short-Term Gain/Loss: This is your reality if you held the short call position for one year or less before closing it. For covered call writers, this is the 99% scenario.

- Long-Term Gain/Loss: While technically possible, this would only happen if you sold a very long-dated option (like a LEAP) and held that short position for more than a year before closing it.

This clean separation is a massive advantage. It gives you the flexibility to actively manage, adjust, and close out your option trades without constantly resetting the holding period on your core stock position. For anyone who doesn't just "set and forget" their calls, understanding this rule is absolutely vital.

Real-World Examples of Covered Call Tax Scenarios

Theory is great, but let's be honest—nothing makes taxes click like seeing the numbers play out. We're going to walk through three common scenarios for a covered call trade to show you exactly how the math works in the real world.

Let's set the stage. Imagine you bought 100 shares of a fictional company, "Innovate Corp" (ticker: INVT), at $90 per share well over a year ago. Your total cost basis is $9,000, and because you've held the stock for more than a year, any profit from selling the shares themselves qualifies for long-term capital gains rates.

You decide it's time to put those shares to work with a covered call income strategy. You sell one call contract against your shares with a $100 strike price that expires in 45 days. For selling this option, you collect a $300 premium ($3.00 per share).

Now, let's see how this one decision can lead to very different tax outcomes.

Scenario 1: The Call Expires Worthless

This is the simplest, and often ideal, outcome. The expiration date rolls around, and INVT stock is trading at $98 per share, which is below your $100 strike price. The option is "out-of-the-money," so it expires worthless. The buyer has no reason to exercise it, and you keep your shares.

- Your Action: You do nothing. The contract simply expires.

- Stock Position: You still own your 100 shares of INVT, and your long-term holding period is untouched.

- Taxable Event: The $300 premium you pocketed is now a realized gain.

Here's the key takeaway: Because the gain came from a short option that expired, the IRS treats it as a short-term capital gain. This profit is taxed at your regular income rate, no matter how long you've owned the underlying stock.

Scenario 2: The Stock Is Assigned (Called Away)

This time, INVT stock has a great month. At expiration, the price is $105 per share—comfortably above your $100 strike price. The option buyer is happy to exercise their right, and your broker automatically sells your 100 shares at the strike price.

To figure out your total profit, you need to add the premium you received to your sale price.

- Effective Sale Price: ($100 Strike Price x 100 Shares) + $300 Premium = $10,300

- Original Cost Basis: $90 x 100 Shares = $9,000

- Total Capital Gain: $10,300 (Sale Price) - $9,000 (Cost Basis) = $1,400

Since you held the INVT stock for more than one year, this entire $1,400 profit is considered a long-term capital gain. This is a huge win from a tax perspective, as long-term gains are taxed at a much friendlier rate.

Scenario 3: You Buy to Close the Call Early

Let's switch things up. Two weeks after you sold the call, INVT's stock price drops to $85. The option you sold has lost most of its value and is now trading for just $50. You decide you want to lock in your profit and get rid of any obligation, so you buy the call back.

- Your Action: You place a "buy to close" order and purchase the contract for $50.

- The Math: $300 (Premium Received) - $50 (Cost to Close) = $250 Profit

- Taxable Event: You've just realized a $250 short-term capital gain.

The gain is short-term because the entire options trade (sell to open, buy to close) happened within a few weeks. Your 100 shares of INVT stock are completely unaffected. You still own them, and their long-term holding period continues to tick up without any interruption.

How to Report Covered Calls on Your Tax Return

Alright, let's move from theory to the practical side of things: taxes. The good news is that you don’t have to do this completely on your own. After the year wraps up, your brokerage will send you a Form 1099-B, which is basically a summary of all your trading activity.

Think of the 1099-B as your cheat sheet for tax season. Your job is to take the numbers from that form and plug them into the right places on your tax return. It’s way less scary than it sounds.

The two main forms you’ll get friendly with are Form 8949 (Sales and Other Dispositions of Capital Assets) and Schedule D (Capital Gains and Losses). Every covered call outcome—whether it expired, got assigned, or you closed it out early—will find its home on these forms.

From Your Broker to the IRS

Your Form 1099-B is the starting point. It lists every single closing transaction with all the key details: dates, proceeds, and your cost basis. This is the raw data you'll work with.

Here’s the basic flow of information:

- Form 1099-B: You get this from your broker. It has everything you need.

- Form 8949: You'll transfer the details for each trade here, splitting them into short-term or long-term categories. For an expired call, you'll list the premium you received as the proceeds and the cost basis as zero.

- Schedule D: This form pulls all the totals from your Form 8949 to calculate your final net capital gain or loss for the year.

A quick heads-up: Brokerages are usually on the ball, but they're not perfect. Always give your 1099-B a once-over and compare it with your own records. Pay close attention to the cost basis for any shares that were assigned—it should be adjusted by the premium you received.

Getting comfortable with how to write covered calls is the first step. To handle the tax side correctly and stay compliant, you'll also need to get familiar with various IRS tax forms. And while this guide should clear up a lot of the confusion, there's no substitute for personalized advice from a tax pro. They can help you avoid common mistakes that might end up costing you.

Common Questions About Covered Call Taxes

Once you get the hang of covered calls, the tax questions naturally follow. It’s one of those areas where a little bit of knowledge can save you a lot of headaches (and money) come tax time. Let's walk through some of the most common questions investors ask.

Does Writing a Covered Call Affect My Stock's Holding Period?

It absolutely can, and this is a big one to watch. When you write a "qualified" covered call—that is, one that isn't deep-in-the-money and has more than 30 days until it expires—your stock's holding period usually isn't affected. The clock just keeps ticking toward that one-year mark for long-term capital gains.

However, if you write a non-qualified call, the IRS can pause your holding period for the underlying stock. That countdown to long-term gains literally stops until the option is closed out or expires. It's a critical detail because it can easily turn what you thought was a long-term gain into a short-term one, which gets taxed at a much higher rate.

What Happens If I Use Covered Calls in an IRA?

Trading inside a tax-advantaged account like a Traditional or Roth IRA is a complete game-changer for taxes. It simplifies everything dramatically.

Any gains you make from collecting premiums or having your shares assigned just grow inside the account—either tax-deferred (Traditional IRA) or completely tax-free (Roth IRA). You don't have to report these individual trades on your annual tax return at all.

Taxes only come into play when you take money out in retirement (for a Traditional IRA). For qualified withdrawals from a Roth IRA, you pay no tax. This is a huge reason why many traders love using these accounts for options strategies.

Can I Use Losses from Covered Calls to Offset Other Gains?

Yes, you can. If you end up closing a covered call for a loss (meaning you bought it back for more than you originally sold it for), that capital loss can be used to offset your capital gains. The IRS has a specific pecking order for this:

- Short-term losses are first used to cancel out short-term gains.

- Long-term losses are first used to cancel out long-term gains.

If you still have net capital losses left over for the year, you can use up to $3,000 of them to reduce your regular taxable income. Any loss beyond that isn't wasted; it can be carried forward to offset gains in future years. It's a valuable tool for managing your overall tax picture.

Stop guessing and start making data-driven decisions. Strike Price provides real-time probability metrics for every strike, helping you balance safety and premium yield. Track your contracts, get smart alerts, and build strategies that align with your income goals. Turn your options trading into a strategic process today at Strike Price.