What Is a Long Put? A Plain-English Guide to Options Trading

If a stock moves past your strike, the option can be assigned — meaning you'll have to sell (in a call) or buy (in a put). Knowing the assignment probability ahead of time is key to managing risk.

Posted by

Related reading

A Step-by-Step Covered Calls Example for Consistent Income

Unlock consistent income with our step-by-step covered calls example. This guide breaks down the strategy, risks, and outcomes to help you trade confidently.

Long Call and Short Put The Ultimate Synthetic Stock Guide

Unlock the power of the long call and short put strategy. This guide explains how synthetic long stock works, its benefits, risks, and how to execute it.

What is a Call Spread? A Clear Guide to Bull and Bear Spreads

What is a call spread? Discover how bull and bear spreads limit risk and sharpen your options trading strategy.

A long put option is a contract that gives you the right, but not the obligation, to sell a stock at a set price on or before a specific date.

Think of it like buying insurance for your stocks. You pay a small fee (called the premium) for protection in case the stock's price tumbles. It's the go-to strategy for traders who are bearish on a stock and believe its price is headed down.

What Is a Long Put in Simple Terms

At its core, buying a long put is a straightforward bet that a stock's price will fall. It’s a defined-risk strategy, which just means the absolute most you can lose is the premium you paid to buy the contract. This makes it a popular alternative to shorting a stock, which comes with the scary potential for unlimited losses.

Before we get too deep, it helps to understand the fundamental principles of how stock options work. Getting those basics down will give you a solid foundation for everything that follows. When you buy a put, you’re essentially locking in a future selling price today.

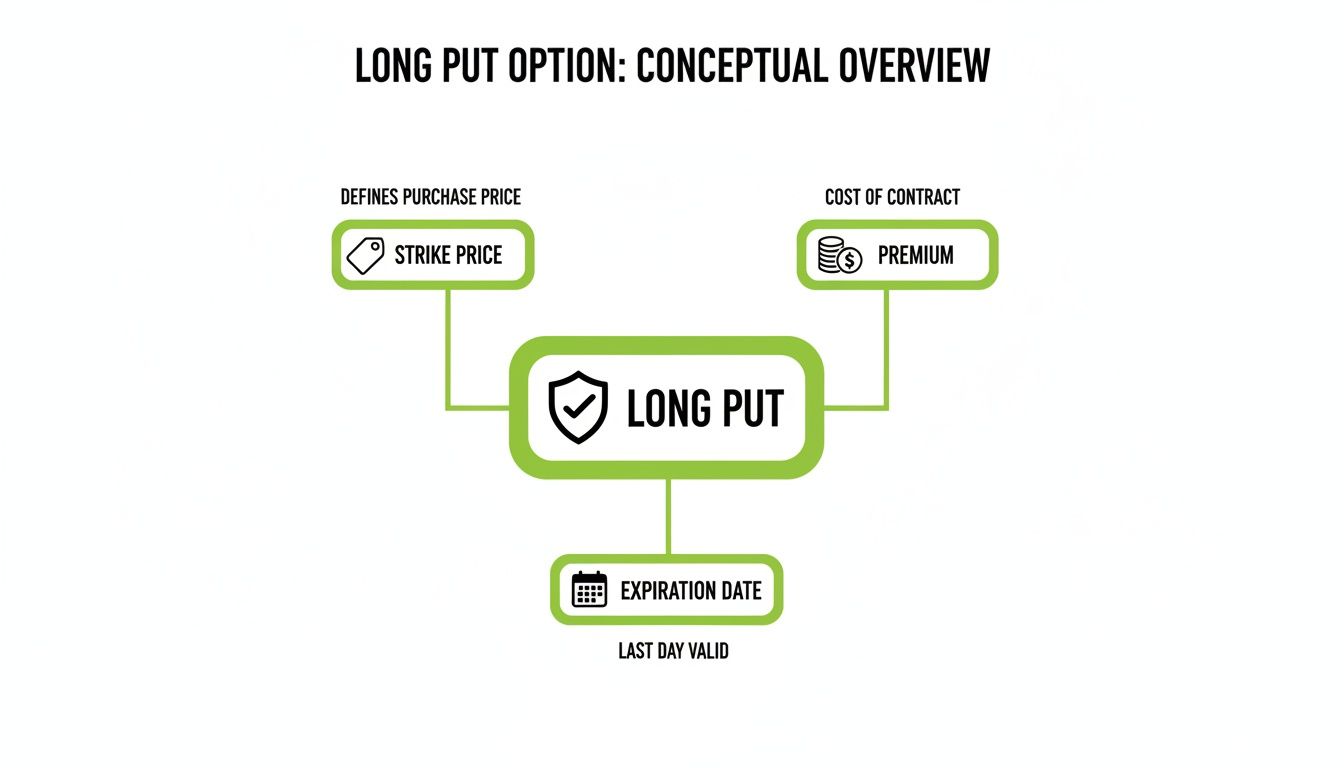

The Key Components of a Long Put

Every put option has three critical pieces that define how it works and what it's worth:

- Strike Price: This is the locked-in price where you have the right to sell the stock. If the stock's market price drops below your strike price, your option starts gaining real value.

- Premium: This is the upfront cost to purchase the put option. It's also the maximum amount of money you can possibly lose on this trade.

- Expiration Date: This is the deadline. The contract expires on this date, so your prediction that the stock will drop has to come true before then for the trade to be profitable.

For a quick overview of these attributes, the table below provides a simple summary.

Long Put Option at a Glance

| Attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| Strategy | Buy a put option. |

| Market Outlook | Bearish (expecting the stock price to fall). |

| Max Profit | Substantial (Strike Price - Premium) x 100. |

| Max Loss | Limited to the premium paid for the option. |

| Breakeven Point | Strike Price - Premium Paid. |

| Primary Use | Speculation on a price drop or hedging a long stock position. |

This table shows just how powerful this strategy can be for the right market outlook.

Let’s put it all together. A long put gives you the right to sell 100 shares of a stock at the strike price until it expires. If you buy one put contract with a $50 strike price for a $3.50 premium, your maximum loss is just $350 ($3.50 x 100 shares).

But if the stock completely tanked and fell to $20, the contract's real value would jump to $3,000, leaving you with a huge profit after subtracting the initial premium.

It's this blend of limited risk and big profit potential that makes the long put such a powerful tool for both speculation and hedging. For a more detailed breakdown of these concepts, check out our guide on how options work.

Visualizing Your Profit and Loss

Talking about long puts in theory is one thing, but seeing how the money works is where it all clicks. The best way to wrap your head around the profit and loss of this strategy is with a payoff diagram—a simple visual map of every possible outcome when the option expires.

The diagram makes two things crystal clear: your risk is strictly limited, but your potential for profit is massive. No matter how high the stock price decides to climb, the most you can ever lose is the premium you paid to get into the trade. On the flip side, as the stock price drops, your profit potential starts to take off.

This graphic breaks down the moving parts that give a long put its value.

Think of these components—strike price, premium, and expiration date—as the terms of an insurance policy. They work together to define your risk and reward, protecting you against a drop in the stock's price.

Calculating Your Breakeven Point

Every long put has a specific price where it flips from a losing trade to a profitable one. This is your breakeven price, and it's a number you absolutely have to know before putting any money down. The good news is, the math is simple.

Breakeven Formula: Strike Price - Premium Paid = Breakeven Price

For the trade to make money by expiration, the stock has to fall below this price. How far it falls below that point determines how much profit you walk away with.

Let's run through a quick example. Say you're bearish on XYZ Corp, which is trading at $98 per share.

- You buy one put option with a $95 strike price.

- You pay a $2.50 premium per share for the contract.

- Your total cost (and maximum risk) is $250 ($2.50 premium x 100 shares).

Using our formula, we can find your breakeven: $95 (Strike Price) - $2.50 (Premium) = $92.50

This means XYZ stock needs to be trading below $92.50 at expiration for your position to turn a profit.

Mapping Out Profit and Loss Scenarios

Now that we have our breakeven point, let's play out a few potential outcomes for this XYZ trade.

Stock Finishes at $90 (Profit): Perfect. The stock dropped well below your $92.50 breakeven. Your option is now worth $5 per share ($95 strike - $90 stock price). After subtracting your cost, your net profit is $250 (($5 option value - $2.50 premium) x 100 shares).

Stock Finishes at $94 (Loss): The stock moved in your direction but didn't quite make it past the breakeven point. The option is worth $1 ($95 - $94). But after factoring in the $2.50 you paid for it, you have a net loss of $150 (($1 option value - $2.50 premium) x 100 shares).

Stock Finishes at $98 (Maximum Loss): The stock went up (or stayed flat), and your option expired worthless because it's above the $95 strike price. You lose the entire premium you paid, hitting your maximum possible loss of $250.

This simple math shows you the clean, defined risk you're taking with a long put. Your downside is always fixed, which gives you a predictable worst-case scenario you can manage from day one.

A Long Put Trade From Start to Finish

Theory is one thing, but watching a trade play out in real time is where the lightbulbs really start to go on. Let's walk through a realistic scenario to see how buying a put option actually works, from entry to exit.

Meet Alex, a trader who’s been keeping an eye on Innovate Corp (ticker: INOV). INOV has had a monster run, with its stock price now sitting at $125 a share. After digging in, Alex feels the stock is overvalued—pumped up by hype—and is due for a pullback after its next earnings report.

Setting Up the Trade

Alex decides to buy a long put to act on this bearish view. The best part? The strategy comes with a clear, defined risk, which is exactly what Alex is looking for.

To find the right contract, Alex pulls up an options chain. If you’re new to this screen, our guide on how to read an option chain will get you up to speed fast.

After scanning the available contracts, Alex lands on one that fits the plan:

- Action: Buy to Open 1 INOV Put Contract

- Strike Price: $120 (slightly out-of-the-money)

- Expiration Date: 45 days from now

- Premium (Cost): $4.00 per share

The total cost to put on this trade is $400 ($4.00 premium x 100 shares per contract). This is also the absolute most Alex can lose.

Key Insight: By picking a strike price below the current stock price, Alex paid a lower premium. The trade-off is that the stock needs to fall further just to break even. This is a classic balancing act between cost and probability.

Next up, Alex needs to figure out the breakeven point to know exactly where the trade flips from red to green.

Breakeven Price = Strike Price - Premium Paid $120 - $4.00 = $116

For this trade to make a single dollar, INOV has to drop below $116 per share before the option expires.

Outcome 1: The Successful Trade

The earnings report comes out, and it’s a dud. Innovate Corp missed its revenue targets and slashed its guidance for the future. As a result, the stock gets hammered, plunging to $105 per share.

Alex’s call was spot on. The put option is now deep in-the-money, and its value has exploded.

- Option Value: $15 per share ($120 strike - $105 stock price)

- Initial Cost: $4 per share

- Net Profit: $11 per share ($15 value - $4 cost)

- Total Profit: $1,100 ($11 x 100 shares)

Alex sells the put contract for $1,500, locking in a $1,100 profit on a $400 investment. That’s a home run.

Outcome 2: The Unsuccessful Trade

Now, let’s rewind and imagine things went the other way. The earnings report is surprisingly good, and a new product announcement sends the stock screaming higher to $135 per share.

Alex’s bearish thesis was dead wrong. With the stock price now miles above the $120 strike, the put option expires completely worthless.

In this case, the trade is a loss, but it's a predictable and controlled one.

- Loss: $400 (the total premium paid for the option)

- Maximum Loss: Reached

While it’s not the outcome anyone wants, the loss was capped at the initial investment. This is the real power of the long put strategy—it lets you take a shot without risking a catastrophic financial blow-up if you’re wrong.

How Traders Use Long Puts in Their Portfolios

Beyond the math and charts, the real power of a long put is its flexibility. Traders use this tool for two core reasons that are polar opposites: playing offense with aggressive bets and playing defense to protect their investments.

On one side, you have the speculator. A long put is their weapon of choice for a high-leverage bet that a stock is going down. It lets them profit from a decline with a small upfront cost and, most importantly, with risk that’s strictly defined. Instead of shorting a stock and facing the nightmare of unlimited losses, a speculator can buy a put knowing the absolute most they can lose is the premium they paid.

On the other side, you have the investor. For them, a long put is a powerful defensive shield. If you’re holding a large position in a stock, buying a put is like taking out an insurance policy on your portfolio. It’s a safeguard against a sudden market crash or bad news hitting that one company.

The Aggressive Play: Speculation

Speculators buy puts to make a simple, directional bet: they believe a stock is headed for a fall. This is a common tactic around big events like earnings reports, new product launches, or major economic news that could send a stock tumbling.

The big advantages for a speculator are pretty clear:

- Limited Risk: No matter how high the stock soars, the maximum loss is capped at the premium paid. That's it.

- Leverage: A small investment in an options premium controls 100 shares of the underlying stock, which can seriously amplify the returns if the price drops.

- Lower Capital Needed: Buying puts is way cheaper and less capital-intensive than shorting the equivalent number of shares.

The Defensive Move: Hedging

Hedging just means using one investment to lower the risk of another. For a long-term investor, buying a put is the classic way to hedge against a drop in the value of their stocks.

Imagine an investor holds 1,000 shares of a big tech company but is getting nervous about a potential market correction. By buying 10 put contracts, they’ve created a safety net. If the stock price plummets, the gains on their put options will help offset the losses on their stock, softening the blow.

This defensive move becomes incredibly popular when the market gets shaky. History shows that demand for puts as portfolio insurance spikes during times of stress. During the 2008 financial crisis and the March 2020 crash, put option volume and the put-to-call ratio shot up as investors scrambled to protect their portfolios. You can even explore how professional traders use options market data for strategic insights.

This dual personality—acting as both a sword for speculators and a shield for investors—is what makes the long put so essential. It gives you a level of control and risk management that simply owning or shorting a stock can’t match.

Navigating the Risks of Buying Puts

While a long put gives you the comfort of a fixed, maximum loss, it's far from a risk-free lunch. You're not just fighting the stock's price movement; you’re also up against a few invisible forces that are constantly working against your position.

Being right about the stock's direction isn't enough. You also have to be right about the timing.

The biggest opponent for any option buyer is time decay, which traders call Theta. Think of Theta as a slow, silent leak in your option's value. Every single day that ticks by, a little bit of your option's premium evaporates into thin air, whether the stock moves an inch or not.

This decay isn't linear; it accelerates like a snowball rolling downhill as the expiration date gets closer. This makes short-term options especially vulnerable to bleeding value quickly. You can dive deeper into how this works in our detailed guide on options time decay.

Understanding the Greeks

To really get a handle on these risks, traders turn to the "Greeks"—a set of values that measure how sensitive your option is to different market factors. They might sound intimidating, but they give you a practical dashboard for understanding how your long put will behave in the real world.

Let's look at the key Greeks that matter most for a long put.

Key Greeks for a Long Put Option

| Greek | What It Measures | Impact on a Long Put |

|---|---|---|

| Delta | How much the option's price moves for every $1 change in the stock price. | A long put has a negative delta. As the stock price drops, your put's value goes up. |

| Theta | How much value the option loses each day due to the passage of time. | Theta is your enemy. It's always negative, chipping away at your premium every single day. |

| Vega | How sensitive the option is to changes in implied volatility. | You want volatility to increase. Higher volatility makes your put more valuable (positive Vega). |

In simple terms, these Greeks tell a story. For your long put to make money, the positive impact from Delta (stock falling) and Vega (volatility rising) needs to be stronger than the constant negative pull of Theta (time decay).

Key Takeaway: For a long put to be profitable, the stock must fall fast enough and far enough to outrun the relentless, negative effect of time decay (Theta). You are in a race against the clock.

Volatility and Pricing Complexity

The price you pay for a put isn't just about the stock price. It's a complex formula driven by the strike price, time until expiration, and—critically—implied volatility.

Across the 1.4 million or more live U.S. equity option symbols, something as simple as a one-point jump in implied volatility can significantly boost the price of puts sitting near the money. This sensitivity, along with the other Greeks, can be measured precisely, helping traders get a much clearer picture of their risk. If you want to see how this plays out with real numbers, optionistics.com has great data on how option prices are determined.

Understanding these dynamics is everything. When you buy a put, you aren't just betting on direction; you're also making an implicit bet on timing and volatility. If the stock just chops sideways or drifts down too slowly, time decay will eat your premium alive and turn what should have been a winning idea into a losing trade.

Common Questions About Trading Long Puts

Once you get the hang of how a long put works, a few practical questions always pop up. Let's tackle the most common ones head-on so you can trade with a bit more clarity.

When Is the Best Time to Buy a Long Put?

The simple answer? When you're convinced a stock is headed down, and you have a good idea why and when. It's not enough to just be bearish; timing is everything. A winning long put trade is often tied to a specific event on the calendar.

Traders usually pull the trigger right before things like:

- An upcoming earnings report they expect to be a dud.

- A bearish chart pattern that looks ready to break down.

- Bad news for the industry or gloomy economic data that could hit a specific stock hard.

It also helps to buy when implied volatility is relatively low, with the expectation it's about to spike. If you buy puts when volatility is already through the roof, you're paying a huge premium, which makes it much, much harder to turn a profit.

How Is a Long Put Different from Shorting a Stock?

Both are bearish plays, but their risk profiles are night and day. When you short a stock, your profit is capped—the stock can only fall to $0. Your potential loss, on the other hand, is technically infinite because there’s no limit to how high a stock can soar.

A long put completely flips that script.

Your absolute maximum loss is the premium you paid for the option. That's it. Your profit potential is still massive, though it's a little less than shorting because you first have to make back the cost of the premium.

In short, a long put is a defined-risk way to bet against a stock. It gives you a level of control that shorting just doesn't offer.

Can I Lose More Than the Premium I Paid?

Nope. And that’s one of the best things about buying options, whether it’s a put or a call. Your risk is locked in from the start. The premium you pay to own the contract is the most you can possibly lose, period.

If the trade goes sideways and the stock is trading above your strike price when the option expires, your put will expire worthless. You’ll be out 100% of the premium you paid (plus commissions), but never a penny more.

How Do I Choose the Right Strike Price and Expiration?

This is where the real strategy comes in, and the right answer boils down to your specific prediction and how much risk you're comfortable with. You’re always juggling cost, probability, and leverage.

Choosing a Strike Price:

- In-the-Money (ITM): These puts (strike is above the stock price) cost more and give you less leverage. The upside? They have a higher chance of staying profitable and aren't as sensitive to the clock ticking down.

- At-the-Money (ATM): These puts (strike is right around the stock price) are a solid middle ground, balancing cost with how much they move when the stock moves.

- Out-of-the-Money (OTM): These puts (strike is below the stock price) are the cheapest and pack the most punch in terms of leverage. But here's the catch: the stock needs to make a big move down just for you to break even, and time decay will eat them alive.

Choosing an Expiration Date:

Options with more time left cost more, but they give your prediction more room to breathe and don't lose value as quickly each day. Short-term options are cheap for a reason—they decay incredibly fast, putting a ton of pressure on you to be right, right now. A good rule of thumb? Buy more time than you think you'll need.

Ready to move from theory to action? Strike Price equips you with the data-driven probability metrics needed to make smarter, more confident options trading decisions. Instead of guessing, use our real-time analytics to find high-probability opportunities and manage risk effectively. Join thousands of traders who are generating consistent income by turning guesswork into a strategic process. Start your journey with Strike Price today and see the difference real data can make. Find your edge at https://strikeprice.app.