What Is a Strangle An Options Trading Guide

If a stock moves past your strike, the option can be assigned — meaning you'll have to sell (in a call) or buy (in a put). Knowing the assignment probability ahead of time is key to managing risk.

Posted by

Related reading

A Step-by-Step Covered Calls Example for Consistent Income

Unlock consistent income with our step-by-step covered calls example. This guide breaks down the strategy, risks, and outcomes to help you trade confidently.

Long Call and Short Put The Ultimate Synthetic Stock Guide

Unlock the power of the long call and short put strategy. This guide explains how synthetic long stock works, its benefits, risks, and how to execute it.

What is a Call Spread? A Clear Guide to Bull and Bear Spreads

What is a call spread? Discover how bull and bear spreads limit risk and sharpen your options trading strategy.

A strangle is an options strategy that lets you profit from a big move in a stock’s price—without having to guess which way it's headed. It involves buying or selling two different options at the same time: an out-of-the-money (OTM) call and an OTM put, both with the same expiration date. This setup makes it a pure bet on volatility.

Decoding the Strangle Strategy

Think of it like betting on a major weather event. You're not sure if the storm will veer north or south, but you're confident it's going to cause a major disruption somewhere. With a strangle, you're not predicting if a stock will go up or down; you’re betting that it will move dramatically one way or the other.

This strategy is built with two distinct "legs"—the call option and the put option. Because both options are out-of-the-money, a strangle is usually cheaper to set up than its close cousin, the straddle, which uses at-the-money contracts. But that lower cost comes with a trade-off: the stock needs to make a bigger move before the trade becomes profitable.

Two Sides of the Volatility Coin

There are two ways to play a strangle, depending on what you think the market will do next. One bets on a breakout, and the other bets on stagnation.

- Long Strangle: You buy both the call and the put. This is a bet on a huge price swing happening soon. Your goal is for the stock to move so sharply that it more than covers the cost of both options you bought.

- Short Strangle: You sell both the call and the put. This is a bet that the stock price will stay calm and trade within the range of your strike prices. If it does, the options expire worthless, and you keep the premium.

A strangle’s purpose is to isolate volatility. It takes directional guesswork out of the equation, letting you focus on the size of an expected price move.

To help clarify the differences, here's a quick side-by-side comparison.

Long Strangle vs Short Strangle at a Glance

| Characteristic | Long Strangle (Buy) | Short Strangle (Sell) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Profit from a large price swing in either direction. | Profit from the stock price remaining stable. |

| Market Outlook | High volatility expected. | Low volatility expected. |

| Max Profit | Unlimited. | Limited to the premium collected. |

| Max Risk | Limited to the premium paid. | Unlimited. |

| Ideal For | Anticipating events like earnings or major news. | Generating income in a sideways or range-bound market. |

As you can see, your choice between buying or selling a strangle comes down to your forecast for volatility.

This guide will break down the mechanics, risks, and rewards of both approaches. We'll get into calculating breakeven points, managing your positions, and figuring out when this powerful strategy might be the right fit for your trading plan.

The Long Strangle: A Bet on Big Moves

Ever look at the market and just know something big is about to happen, but you’re not sure which way it’ll break? That’s the perfect time for a long strangle.

Think of it as placing a bet on a major breakout. You’re setting yourself up to profit from a massive price swing—whether the stock rockets higher or craters lower. It's the go-to strategy for high-volatility events like earnings reports, product launches, or FDA decisions.

The mechanics are refreshingly simple: you simultaneously buy an out-of-the-money (OTM) call option and buy an OTM put option on the same stock with the same expiration date. By owning both, you've created a position that wins as long as the stock doesn't just sit still.

Constructing the Trade

Let's walk through an example. Imagine a company, "TechCorp" (TCORP), is trading at $100 per share and has a huge announcement next month. You think the news will send the stock flying, but the direction is a coin toss.

Here's how you could set up a long strangle:

- Buy a $110 call option: This gives you the right to buy TCORP at $110. It only pays off if the stock surges way past that price.

- Buy a $90 put option: This gives you the right to sell TCORP at $90. This one pays off if the stock tumbles well below that mark.

Let’s say the call costs you $2.00 per share ($200 per contract) and the put costs $1.50 per share ($150 per contract). Your total upfront cost—your premium—is $3.50 per share ($350). That's it. That $350 is also your absolute maximum loss.

The real beauty of a long strangle is its defined risk and theoretically unlimited profit potential. Your loss is capped at the premium you paid, but if the stock makes an explosive move, your gains have no ceiling on the upside and can be huge on the downside.

The main reason we use OTM options here is to keep costs down. A long strangle, by definition, uses an OTM call and an OTM put. This makes it a much cheaper way to bet on volatility compared to a straddle, which uses more expensive at-the-money options. You're often looking at a cost reduction of 20–60%, giving you a better risk-reward profile on a big move. You can play around with different scenarios using this options profit calculator from InsiderFinance.io.

Calculating Your Breakeven Points

For a long strangle to make money, the stock has to move far enough to cover the total premium you paid. Because you're betting on a move in either direction, you have two breakeven points.

Let's stick with our TCORP example:

- Upside Breakeven: Call Strike Price + Total Premium Paid = $110 + $3.50 = $113.50

- Downside Breakeven: Put Strike Price - Total Premium Paid = $90 - $3.50 = $86.50

This means for your trade to be profitable, TCORP stock must either climb above $113.50 or drop below $86.50 by the expiration date. If the price lands anywhere between those two points, you'll lose money. The maximum loss of $350 happens if the stock price finishes between your two strike prices of $90 and $110.

The Role of Implied Volatility

Here's the secret sauce for a successful long strangle: implied volatility (IV). IV is simply the market's best guess about how much a stock will swing in the future. When IV is high, options are expensive. When it's low, they're cheap.

The absolute best time to buy a long strangle is when implied volatility is low. Why? Because it lets you buy both the call and the put for a bargain, which does three crucial things:

- It lowers your total risk (the premium you have to pay).

- It brings your breakeven points closer together, widening your potential profit zone.

- It boosts your potential return if volatility shoots up after you've entered the trade.

If you buy a strangle when IV is already sky-high (like minutes before an earnings call), you're paying top dollar. Even if you correctly predict a big move, you can still lose money if it wasn't as big as the market priced in. This is called "IV crush"—when volatility collapses after the event, sucking the value right out of your options.

The Short Strangle: A Bet on Stability

While a long strangle is a bet on a huge price swing, the short strangle is its mirror image. It's a strategy designed to profit when the market is calm and a stock is expected to trade sideways.

If you think a stock is likely to stay within a predictable range, selling a strangle lets you collect an upfront premium for making that bet. Think of it like selling insurance. You collect a payment (the premium) from someone worried about a big move. As long as that move doesn't happen—meaning the stock price stays between your two strike prices—you simply keep the cash.

How the Short Strangle Works

To set up a short strangle, you simultaneously sell an out-of-the-money (OTM) call option and sell an OTM put option on the same stock, with the same expiration date. The moment you sell them, you receive a cash credit in your account. That credit is your maximum possible profit.

Let's stick with our "TechCorp" (TCORP) example, which is trading at $100. You believe the stock won't make any big moves over the next month.

- Sell a $110 call option: You collect a premium of, say, $2.00 per share. This means you're obligated to sell TCORP at $110 if the buyer exercises it.

- Sell a $90 put option: You collect another premium, maybe $1.50 per share, and agree to buy TCORP at $90 if that option is exercised.

Your total credit is $3.50 per share, or $350 for one set of contracts ($3.50 x 100 shares). This $350 is the absolute most you can make on the trade, and you get to keep all of it if TCORP closes anywhere between $90 and $110 at expiration.

The High-Probability, High-Risk Tradeoff

The short strangle is often called a high-probability strategy. Because you’ve created such a wide profit range, the stock has plenty of room to bounce around without causing you to lose money. But this high probability comes with a dangerous catch: asymmetric risk.

A short strangle's profit is strictly capped at the premium you collect, but its potential for loss is substantial and theoretically unlimited. This is not a strategy for the faint of heart or the undercapitalized trader.

This lopsided risk profile is exactly why brokers have strict margin requirements for this trade. While it’s a favorite among income-focused options traders, the risk is very real. Your maximum profit is the premium you were paid, but your losses can be massive. If the stock rallies hard, your upside loss is theoretically infinite. If it crashes toward zero, your downside loss is enormous. The team at tastylive offers some great educational content on the mechanics of strangles if you want to learn more.

Ideal Conditions and Breakeven Calculations

The absolute best time to sell a strangle is when implied volatility (IV) is high. High IV pumps up option premiums, which means you get paid more for taking on the exact same risk. This higher credit does two wonderful things for your trade:

- Increases Your Maximum Profit: A bigger upfront premium means a bigger potential payday.

- Widens Your Breakeven Points: The higher credit pushes the prices where you start losing money further apart, giving you a much larger buffer for the stock to move.

Figuring out your breakeven points is absolutely critical for managing your risk.

- Upside Breakeven: Short Call Strike + Total Premium Received = $110 + $3.50 = $113.50

- Downside Breakeven: Short Put Strike - Total Premium Received = $90 - $3.50 = $86.50

As long as TCORP's stock price stays between $86.50 and $113.50 at expiration, your trade will be profitable. That wide range is the main reason this strategy is so popular.

A short strangle is also a bet on time. Every day that goes by, the options you sold lose a little bit of value due to time decay, or Theta. This erosion works in your favor, making the position cheaper to buy back. If you want to dive deeper, you can explore the powerful effects of options time decay in our dedicated guide.

Strangle vs Straddle: Key Differences for Traders

Traders often throw the terms "strangle" and "straddle" around like they're interchangeable, but that’s a rookie mistake. While they’re both non-directional plays on volatility, their setup, cost, and risk profiles are worlds apart. Knowing these differences is critical to picking the right tool for what you think the market’s about to do.

At its heart, the difference between a strangle and a straddle comes down to one thing: the strike prices you choose. That single decision changes everything—from what you pay upfront to your breakeven points and your overall shot at making a profit.

Strike Price: The Defining Factor

The split between the two strategies is simple but has massive implications. A straddle uses the same at-the-money (ATM) strike for both its call and put. A strangle, on the other hand, uses different out-of-the-money (OTM) strikes.

- Straddle: You buy (or sell) a call and a put with the exact same strike price, usually whatever’s closest to the stock’s current price.

- Strangle: You buy (or sell) a call with a higher strike price and a put with a lower one, creating a wide "range" around the current price.

This is the key. Grasp this structural difference, and all the other trade-offs will make perfect sense.

Cost vs. Probability: A Strategic Trade-Off

Because a strangle uses OTM options—which have zero intrinsic value—it’s always cheaper to put on than a straddle. ATM options cost more because they have a much higher chance of finishing in-the-money. This lower upfront cost is the main reason traders choose a strangle.

A strangle is the lower-cost, lower-probability cousin to a straddle. You risk less premium, but you need a much bigger move in the stock to see a profit.

But that lower cost comes with a catch. Since the strikes are farther from the current stock price, a strangle needs a huge price swing to become profitable. The stock can’t just move; it has to move past your much wider breakeven points. A straddle, with its tight ATM strikes, starts making money with a smaller move.

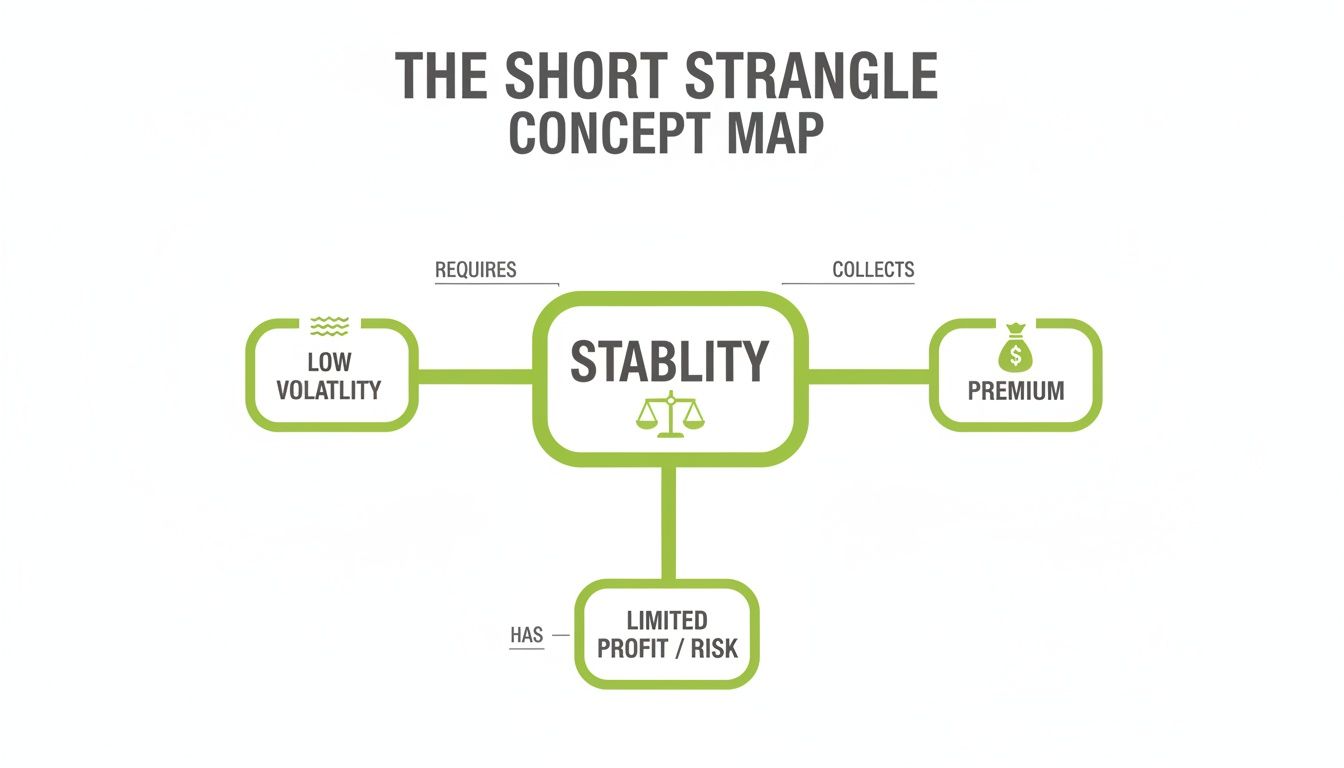

This visual breaks down the core concepts for the short strangle, a strategy that relies on stability to collect premium.

As the map shows, the short strangle is all about betting on stability. The goal is for the stock to stay put so the seller can pocket the premium in a low-volatility environment.

Strangle vs Straddle: A Head-to-Head Comparison

Let's put these two strategies side-by-side to make the decision clearer. The table below breaks down the critical differences to help you decide which one aligns with your market outlook and risk tolerance.

| Feature | Strangle (OTM Options) | Straddle (ATM Options) |

|---|---|---|

| Upfront Cost | Lower premium paid or received. | Higher premium paid or received. |

| Breakeven Points | Wider apart, requiring a larger price move to profit. | Closer together, requiring a smaller price move to profit. |

| Probability of Profit | Lower probability of the stock moving past breakevens. | Higher probability of the stock moving past breakevens. |

| Impact of Theta | Less severe time decay due to lower premium. | More severe time decay due to higher premium. |

| Best Use Case | Expecting a very large move but want to reduce cost. | Expecting a significant move but unsure of the magnitude. |

So, which one is for you? It all boils down to your conviction. If you're confident a big move is on the horizon and want to maximize your odds of being right, the pricier straddle is probably your best bet. But if you think the coming move will be explosive and you want to make a cheaper bet on that volatility, the strangle offers a lower-cost entry with a higher potential return on your money.

How to Manage Your Strangle Position

Putting on a strangle is just the first step. The real skill—and where the money is made or lost—comes from managing the trade once it's live.

Markets don't stand still. What looks like a safe, profitable trade one day can turn against you in a heartbeat if you're not paying attention. This is where a solid feel for the option Greeks becomes your best friend.

Think of the Greeks as your trade's dashboard. They give you a live read on how sensitive your position is to shifts in stock price, time, and volatility. Mastering them is non-negotiable for navigating a trade and knowing when (and how) to make smart adjustments.

Watching Your Deltas: The Directional Compass

When you first open a strangle, long or short, your position is delta neutral. This is a fancy way of saying its value isn't really affected by small up-or-down ticks in the stock price. You've essentially placed a bet on volatility, not direction.

But that neutrality doesn't last. As the stock price starts to move, your position will start picking up delta, and with it, directional risk.

- If the stock price rises toward your call strike, your position's delta will turn positive. Your strangle will start behaving a lot more like a long stock position.

- If the stock price falls toward your put strike, your delta will swing negative. Now, it's acting more like a short stock position.

This "delta drift" is your signal that the trade's risk profile has changed. For short strangle sellers, a big move can quickly expose you to directional risk you never wanted. Active management means keeping an eye on these shifts and deciding when it’s time to step in.

Vega and Theta: The Heart of the Strangle

While delta tracks direction, Vega and Theta are the real engine of a strangle. They represent the two core forces you're betting on: volatility and time.

Vega is all about sensitivity to implied volatility (IV). For a strangle trader, it's arguably the most important Greek to watch.

- Long Strangle: You have positive Vega. This is great news if volatility spikes. Your options get more expensive, and your position gains value, even if the stock hasn't moved much.

- Short Strangle: You have negative Vega. Your goal is for volatility to drop. You profit from the "IV crush" that often happens after big events like earnings, making the options you sold cheaper.

Theta is the predictable grind of time decay. It's the constant force that eats away at an option's value, day after day.

- Long Strangle: You have negative Theta, making time your enemy. Every day that goes by without a big price move, your options are bleeding value and cutting into your potential profit.

- Short Strangle: You have positive Theta, making time your best friend. The daily decay on the options you sold is exactly how you make money, as long as the stock price behaves.

For a deeper look into all the Greeks and how they work together, our complete guide on what are option Greeks is a must-read for any serious options trader.

Common Adjustments to Manage Risk

When a trade starts to go against you, you don't have to just sit on your hands and hope for the best. Proactive traders use adjustments to defend their position, cut down risk, and give themselves a better chance of success.

Here are a few of the go-to moves:

- Rolling the Untested Side: If the stock moves hard toward one of your strikes (the "tested" side), you can roll the other strike closer. For a short strangle, if the stock tanks toward your put, you could roll the call strike down to collect more premium. This extra cash widens your breakeven point on the downside, giving you more room to be right.

- Rolling Up or Down with the Stock: This involves moving the entire strangle. If the stock rallies and blows past your call strike, you might close the current trade and open a new one with higher strikes, essentially re-centering your position around the new stock price.

- Rolling Out in Time: If you're running out of time before expiration and the trade isn't profitable—but you still believe in your original thesis—you can "roll" the whole position to a later expiration date. This buys you more time for the trade to work out and usually lets you collect a bit more premium in the process.

The goal of an adjustment isn't always to turn a loser into a huge winner. It’s about risk management. It's about cutting your potential loss, improving your breakeven points, and giving yourself a better shot at scratching the trade or even walking away with a small profit.

Effectively managing a strangle often involves more advanced techniques, like using data analytics for risk hedging to model different outcomes. At the end of the day, knowing when and how to adjust is what separates the pros from the novices.

Essential Considerations Before You Trade Strangles

Alright, you’ve seen the payoff diagrams and understand the theory. Before you jump in and place your first strangle trade, we need to talk about the real-world variables that can trip up even the most prepared traders.

Think of this as your final pre-flight check. Getting these details right is what separates traders who consistently pull in profits from those who get blindsided by costs and risks they never saw coming.

The Hidden Costs of Commissions

First up, commissions. While most brokers have dropped commissions for stock trading, options are a different story. You’ll almost always pay a per-contract fee. Since a strangle has two legs—a put and a call—you get hit with that fee twice when you open the trade and twice again when you close it.

That might not sound like a big deal, but it adds up fast. For strangles on lower-priced stocks or trades where you’re only collecting a small premium, commissions can take a huge bite out of your profit. Always do the math. A $0.50 credit per share looks a lot less attractive after you subtract $2.60 for the round trip ($0.65 per leg, times four).

Understanding Liquidity and Spreads

Not all stocks are good candidates for a strangle. The single most important factor is liquidity—how easily you can get in and out of a trade without your own order moving the price. The best way to gauge this is by looking at the bid-ask spread. That’s the tiny gap between what buyers are willing to pay and what sellers are willing to accept.

If you’re trading options on an illiquid stock, that spread will be wide. It’s like an invisible tax you pay every time you trade, eating into your profits on both entry and exit. To avoid this "slippage," stick to stocks and ETFs that have a ton of daily options volume. That’s how you know you’re getting a fair price.

A key prerequisite for trading strangles is developing a comprehensive understanding of market volatility and its impact on options pricing. This knowledge helps you anticipate market behavior and select appropriate assets for your strategy.

The Critical Risk of Early Assignment

If you’re selling short strangles, this is the big one. Assignment risk is the monster under the bed for many new premium sellers, and it’s often misunderstood. Assignment is when the person who bought your option decides to exercise their right—forcing you to either buy (on a put) or sell (on a call) the underlying stock at the strike price.

While this can technically happen at any time, it’s most common when an option is deep in-the-money. If your short put gets assigned, you suddenly own 100 shares of the stock per contract. If your short call is assigned, you’re now short 100 shares. In an instant, your neutral, non-directional trade becomes a directional one with a completely different risk profile. Learning to manage an unexpected assignment is a non-negotiable skill. A critical part of this is knowing how to calculate implied volatility, which directly influences an option's extrinsic value and its likelihood of being exercised early.

Common Questions About the Strangle Strategy

Even after you get the mechanics down, some questions always pop up when it's time to actually put a strangle to work. Let's tackle the most common ones and clear up any lingering confusion.

When Is the Best Time to Use a Long Strangle?

The perfect setup for a long strangle is right before a big, binary event where the outcome is anyone's guess. Think about an upcoming earnings report, a make-or-break FDA decision for a biotech company, or a major court ruling.

You want to get into the trade when implied volatility (IV) is still pretty low. A lower IV means the options—both the call and the put—are cheaper to buy. Your goal is to get positioned for a price explosion that’s way bigger than what the market is currently pricing in. This way, you profit not just from the stock's move, but also from the IV spike that almost always follows the news.

Key Takeaway: Buy a long strangle when you're expecting a massive price swing and implied volatility is low. You're essentially betting that the market is underestimating just how wild the reaction will be.

What Is the Biggest Risk of a Short Strangle?

The number one risk of a short strangle—and it's a big one—is its undefined loss potential. Because you’re selling naked options, a huge, unexpected move past either of your strike prices can lead to catastrophic, theoretically unlimited losses.

The risk is completely lopsided. Your profit is capped at the premium you collected when you sold the options, but your potential loss is not. If the stock rockets higher, the risk on your short call is infinite. If it tanks toward zero, the risk on your short put is massive. This is exactly why the strategy demands a ton of margin and is really only for experienced traders with ironclad risk management rules.

How Do I Choose the Right Strike Prices for a Strangle?

Picking the right strikes is an art, a delicate balance between the premium you can collect, the risk you're taking on, and the probability of success. There's no single "right" answer here; it all comes down to your read on the market and how much risk you're comfortable with.

Here are a few common ways traders approach it:

- Probability-Based Strikes: A very popular method for short strangles is selling strikes that are one standard deviation away from the current price. Statistically, this gives the trade a high probability of expiring worthless, letting you just keep the premium.

- Delta as a Guide: Many traders use an option's Delta as a rough proxy for probability. A common rule of thumb is to sell strikes with a Delta somewhere between 0.15 and 0.30. This usually strikes a good balance between collecting a respectable premium and giving yourself a wide profit range.

- Event-Driven Strikes: For a long strangle, you might look at how the stock has moved around similar events in the past (like previous earnings calls) to get a feel for a realistic move. Then, you'd place your strikes just outside that expected range to catch the breakout.

Ultimately, your strike selection should be a direct reflection of your conviction about the coming volatility.

Ready to stop guessing and start trading with data-driven confidence? Strike Price provides real-time probability metrics for every strike price, turning options selling into a strategic, income-generating process. Join thousands of traders who use our smart alerts and analytics to balance safety and yield.