What is short call: A Practical Guide to Generating Income

If a stock moves past your strike, the option can be assigned — meaning you'll have to sell (in a call) or buy (in a put). Knowing the assignment probability ahead of time is key to managing risk.

Posted by

Related reading

A Step-by-Step Covered Calls Example for Consistent Income

Unlock consistent income with our step-by-step covered calls example. This guide breaks down the strategy, risks, and outcomes to help you trade confidently.

Long Call and Short Put The Ultimate Synthetic Stock Guide

Unlock the power of the long call and short put strategy. This guide explains how synthetic long stock works, its benefits, risks, and how to execute it.

What is a Call Spread? A Clear Guide to Bull and Bear Spreads

What is a call spread? Discover how bull and bear spreads limit risk and sharpen your options trading strategy.

A short call is an options strategy where you sell someone the right, but not the obligation, to buy a stock from you at a set price, by a certain date. In exchange for selling that right, you get paid a cash premium upfront. It's a popular way for investors to generate a steady stream of income from stocks they already own.

What a Short Call Really Is, in Simple Terms

Think of it like selling a binding "rain check" on 100 shares of stock you own. You set the sale price (the strike price) and an expiration date for the offer.

A buyer pays you a non-refundable fee (the premium) just for the right to hold that rain check. This initial transaction, where you collect cash for creating the contract, is called a sell-to-open order.

Once you've sold the call, only two things can happen. It's that simple.

The Two Potential Outcomes

The most common outcome is that the stock's price stays below your agreed-upon sale price. The buyer's rain check is worthless—why would they buy from you when they can get it cheaper on the open market? When the contract expires, you just keep the premium as pure profit. No strings attached.

The second outcome happens if the stock price climbs above your strike price. The buyer will likely "exercise" their rain check, which forces you to sell your 100 shares at that locked-in price. You might miss out on gains above that price, but you still keep the premium you collected, and you successfully sold your stock at a price you were happy with.

To help you keep track of the moving parts, here’s a quick summary of the short call basics.

Short Call Fundamentals at a Glance

This table breaks down the core components of the strategy from your perspective as the seller.

| Component | Your Role (Seller/Writer) | Your Obligation | Primary Goal | Maximum Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Short Call | You are selling the right for someone else to buy your stock. | To sell 100 shares of the underlying stock at the strike price if assigned. | To collect premium income while the stock stays below the strike price. | The premium you received when you sold the call. |

This clear, straightforward mechanism is what allows traders to generate a reliable income stream. By repeatedly selling these "rain checks" on stocks you hold, you can collect premiums month after month, boosting your portfolio's overall returns.

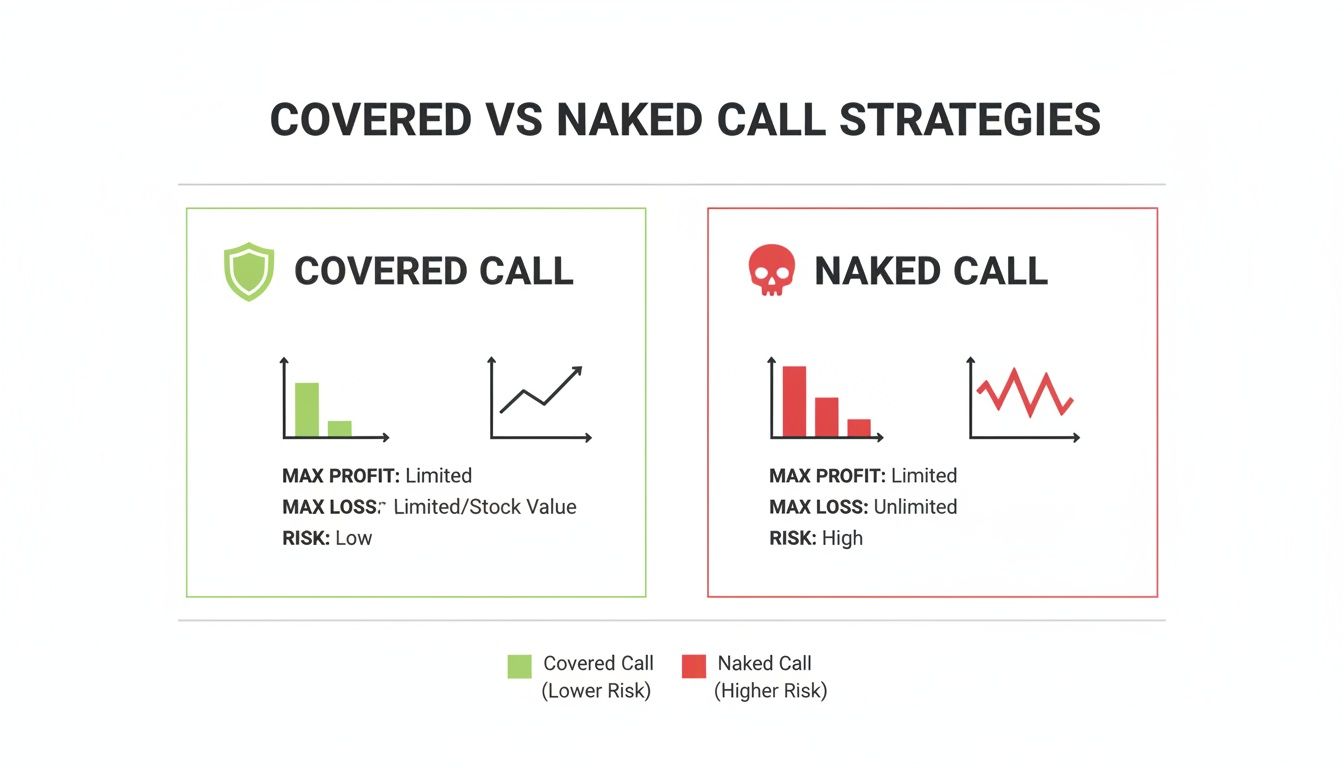

The Critical Difference: Naked vs. Covered Calls

Not all short call strategies are created equal. Far from it. Understanding the difference is absolutely fundamental to your financial safety, because it separates a conservative income strategy from a high-stakes, speculative gamble.

It all comes down to one simple question: Do you actually own the underlying stock?

The two main flavors of short calls are naked calls and covered calls. While both involve selling a call option to collect a premium, their risk profiles couldn't be more different. One is a favorite among income-focused investors, while the other is reserved for the most experienced, high-risk traders.

The Covered Call: A Prudent Approach

A covered call is exactly what it sounds like—your obligation to sell shares is "covered" because you already own them. To sell a covered call, you must first own at least 100 shares of the underlying stock for each call contract you sell.

By owning the shares, you’re always prepared to deliver them if the option gets exercised. Your risk isn't that the stock will soar to the moon; it's simply the opportunity cost of missing out on gains above the strike price. If the stock skyrockets, you don't face a catastrophic loss. You just sell your shares at the agreed-upon price, and you still get to keep the premium you collected upfront.

For many investors, the covered call is a cornerstone strategy for generating consistent income. It turns a stock you already hold into a small, cash-generating asset, much like renting out a property you own.

The Naked Call: A High-Stakes Gamble

In sharp contrast, a naked short call is sold without owning the underlying 100 shares. You are literally selling a promise to deliver shares that you don't have. This is where the real danger lies.

If the stock price stays below the strike price, everything is fine. You just keep the premium, and the trade is a success.

But if the stock price rises significantly above the strike price, you have a massive problem on your hands. To fulfill your end of the bargain, you’d be forced to buy 100 shares on the open market at the new, much higher price, only to immediately sell them for the lower strike price.

Because a stock's price can theoretically rise indefinitely, the potential loss on a naked short call is unlimited. This is absolutely not a strategy for beginners. In fact, it's so risky that most brokerage accounts require special permissions and a significant amount of capital just to attempt it.

Covered Call vs Naked Call Comparison

To make the distinction crystal clear, let's put these two strategies side-by-side. The table below breaks down the core differences in risk, reward, and what's required to place the trade.

| Attribute | Covered Short Call | Naked Short Call |

|---|---|---|

| Requirement | Own at least 100 shares of the underlying stock. | No stock ownership required, but significant margin is. |

| Maximum Loss | Limited (opportunity cost of missing gains). | Unlimited. Potentially catastrophic. |

| Primary Goal | Generate consistent income from existing holdings. | Speculate on a stock's price falling or staying flat. |

| Common Use | A conservative strategy favored by income investors. | A highly speculative strategy for advanced traders. |

Ultimately, the choice comes down to risk management. The covered call is a calculated method for earning a little extra yield on your portfolio. The naked call, on the other hand, is a pure bet against a stock's rise—with a risk that can far outweigh the premium you collect.

How to Visualize Your Profit and Loss

Theory is one thing, but seeing how a short call trade actually plays out is another. The best way to get a feel for your potential profit and loss is with a simple payoff diagram. It’s a graph that instantly makes the risk-reward tradeoff clear, showing you exactly how your position will perform as the stock price moves.

When you sell a call, your best-case scenario is always capped at the premium you collect upfront. That’s your maximum profit, and you lock it in if the stock price finishes at or below the strike price when the option expires. On the graph, this looks like a flat, horizontal line—your peak earnings.

Your trade stays profitable as long as the stock doesn't rally too far past your strike.

Calculating Your Breakeven Point

The breakeven price is the magic number where you neither make nor lose money at expiration. For a short call, the math is simple:

Breakeven Price = Strike Price + Premium Received Per Share

If the stock moves above this price, your position starts to lose money. For every dollar the stock climbs past your breakeven point, you lose a dollar. This is why selling calls is a neutral-to-bearish strategy; you win when the stock stays put, drops, or only climbs a little bit.

The infographic below really drives home the difference between selling a call that’s covered versus one that’s naked.

This visual shows why a covered call (the shield) is a defined-risk income strategy, while a naked call (the skull) opens you up to potentially unlimited losses. Grasping this distinction is probably the most important risk management lesson for anyone learning what a short call is.

How to Choose the Right Strike Price with Confidence

Picking the right strike price for a short call is where the real strategy kicks in. It's easily the most important decision you'll make, since it directly controls both your potential income and how much risk you're taking on. Guessing isn't a strategy — using data is.

Instead of just picking a number that feels right, successful option sellers think in probabilities. They start with one simple question: "What's the statistical chance this stock actually hits my strike price before expiration?"

Answering that question turns the trade from a coin flip into a calculated risk.

Using Delta as Your Probability Guide

The best tool for the job here is Delta, one of the core "Greeks" in the options world. While Delta wears a few different hats, for a short call seller, it gives you a surprisingly accurate, real-world estimate of an option’s probability of expiring in-the-money (ITM).

It's pretty straightforward:

- A call option with a 0.30 Delta has roughly a 30% chance of expiring ITM.

- A call option with a 0.15 Delta has roughly a 15% chance of expiring ITM.

That means a 0.15 Delta call also has an 85% probability of expiring worthless — letting you walk away with the entire premium you collected. If you want to go deeper on this vital metric, check out our full guide on what Delta in option trading is. This is the cornerstone of generating consistent income.

When you frame your decision around Delta, you stop hoping for an outcome and start selecting a trade with a known probability of success. It’s about aligning every single trade with your personal risk tolerance.

This isn't just theory, either. Looking at options data going all the way back to 1996, we can see that traders who systematically pick strikes based on probability metrics consistently outperform those who just use fixed distances from the stock price. This is exactly how sophisticated options statistics platforms use probability data to give traders an edge.

Balancing Premium Income with Risk

The relationship between Delta, premium, and risk is a constant balancing act. Picking your strike is all about finding the sweet spot that works for you.

- Higher Delta (e.g., 0.40): This strike is closer to the current stock price. You'll collect a much fatter premium, but you're also looking at a higher (~40%) chance of having your shares called away. It's a more aggressive, income-first approach.

- Lower Delta (e.g., 0.20): This strike is further away from the action. The premium you get will be smaller, but the probability of assignment drops to around 20%. This is the more conservative, safety-first choice.

Ultimately, there's no single "best" strike price. There's only the one that's best for you. By using Delta as your guide, you can confidently pick a short call that perfectly matches the income you want with the risk you're willing to take.

Managing Volatility and the Risk of Assignment

As a short call seller, you're constantly navigating two powerful forces: market volatility and the risk of assignment. Learning to handle both is what separates a disciplined strategy from a series of hopeful guesses.

First, let's clear up what assignment really is. It simply means the buyer of your call option decided to exercise their right, forcing you to sell them 100 shares at the strike price. For a covered call seller, this isn't a catastrophe—it's one of the potential outcomes you planned for. You sold your stock at your target price and you kept the premium.

But sometimes, an assignment you weren't expecting can throw a wrench in your plans. This often happens with dividend-paying stocks right before their ex-dividend date, as buyers exercise their calls to snag the upcoming dividend payment for themselves.

The Double-Edged Sword of Volatility

Volatility is the engine that powers option premiums. When a stock is making big, wild price swings, the uncertainty drives up the price of options contracts. For a seller, this is fantastic news.

During periods of high implied volatility, you can find premiums that are 30-50% higher than what you'd see in a quiet market. That extra cash can seriously improve the risk-reward math on your trade. But remember, that higher reward comes with higher risk—volatility means the stock is more likely to make a big, unexpected move against you.

Volatility is your friend as an options seller, but it demands respect. Higher premiums are your compensation for taking on higher uncertainty. Your job is to decide if the compensation is worth the risk.

Proactive Management Techniques

Instead of just reacting to the market, you can use a few simple techniques to stay in the driver's seat.

Here are a few actionable tips to keep you in control:

- Avoid Earnings Reports: Never sell calls that expire right after a company’s earnings announcement. These events are famous for creating huge, unpredictable price gaps overnight, turning what looked like a safe trade into a massive headache.

- Watch Ex-Dividend Dates: If you don't want your shares called away, keep a close eye on ex-dividend dates. To be safe, consider closing your short call position a day or two before that date to eliminate the assignment risk.

- Use Shorter Expirations: Selling calls that expire in 30-45 days is often the sweet spot. This window lets you capture the fastest period of time decay (theta decay) without exposing yourself to too much long-term market drama.

And if a trade does start to move against you? Don't panic. You're not stuck. You can often adjust your strike price or expiration date to manage the position. This powerful technique, known as rolling over options, can help you turn a potential loss into a future win.

A Real-World Covered Call Example Step by Step

Let's put all this theory into practice. Sometimes the best way to understand a strategy is to walk through it, number by number.

Imagine an investor named Alex. He owns 100 shares of a popular tech stock, let's call it XYZ Inc., which is currently trading at $145 per share.

Alex feels pretty good about XYZ long-term, but for the next month, he thinks the stock is more likely to trade sideways than make a huge move up. He decides to sell a covered call to squeeze some extra income out of his shares while he waits.

The Trade Setup

Alex logs into his brokerage account and pulls up the option chain for XYZ. He's not looking to gamble; he wants a high probability of keeping his shares and the premium. This means he's hunting for a strike with a low Delta.

He finds a call option with a $155 strike price that expires in 35 days. Perfect.

The Delta is 0.20, which tells him there's roughly an 80% probability the option will expire worthless. The premium is $1.50 per share.

Alex sells one contract (since he owns 100 shares) and instantly sees a $150 credit hit his account ($1.50 premium x 100 shares). That's his maximum profit on this trade, and it's his to keep no matter what happens next.

For a deeper look into the mechanics of setting up these trades, check out this a comprehensive guide to selling covered calls.

The Three Potential Outcomes

Fast forward 35 days. As the expiration date arrives, one of three things will happen with Alex's trade:

XYZ stays below $155: This is the ideal scenario. The option expires worthless, and the buyer has no reason to exercise it. Alex keeps his 100 shares of XYZ and the entire $150 premium he collected. Pure profit. He's now free to sell another call for the next month.

XYZ rises above $155: The stock had a good month. The option is now "in-the-money," and Alex gets assigned. He is obligated to sell his 100 shares at the agreed-upon $155 strike price. He still keeps the premium, so his total gain is the $10 per share capital appreciation ($155 sell price - $145 cost basis) plus the $1.50 premium per share. That’s a total profit of $1,150. He missed out on gains above $155, but he still locked in a solid return.

XYZ stock price falls: The stock takes a dip. On paper, his 100 shares are worth less than when he started. However, the $150 premium he collected helps offset some of that unrealized loss. The call option expires worthless, so he keeps the cash and his shares, effectively lowering his cost basis.

Common Questions About Selling Short Calls

When you're just starting out, a few questions always seem to pop up. Let's tackle some of the most common ones to make sure these core concepts are crystal clear.

Can I Close a Short Call Before It Expires?

You bet. You can get out of the trade at any time by placing a "buy-to-close" order. This is just the opposite of your opening trade—you're simply buying back the exact same call option you sold.

Why would you do this? Two big reasons. First, to lock in a profit. If the option's price has dropped nicely, you can buy it back for cheap and pocket the difference. Second, to cut your losses. If the stock starts climbing and making you nervous, you can buy the call back before things get out of hand.

What Happens If My Short Call Is Assigned Early?

Early assignment just means the buyer of your call wants to exercise their right to buy your shares before the expiration date. When this happens, you'll see 100 shares of the stock leave your account, and the cash from the sale will show up in its place.

If you sold a covered call, this isn't a bad thing at all. It's actually the best-case scenario—you've hit your maximum profit on the trade, just a little sooner than planned. This tends to happen most often with dividend-paying stocks right before the ex-dividend date, as buyers exercise their options to make sure they get that upcoming dividend payment.

Assignment isn't something to fear when you're selling covered calls. It's one of the two planned outcomes, confirming you successfully sold your stock at your target price.

Is Selling a Call the Same as Shorting a Stock?

Not at all. They're completely different strategies with opposite goals and risk profiles.

Shorting a stock is an aggressive, bearish bet. You're borrowing shares and selling them, hoping the price goes to zero. It comes with unlimited risk because there's no ceiling on how high a stock's price can go.

Selling a covered call, on the other hand, is a conservative income strategy. You're getting paid a premium to agree to sell your shares at a specific price. Your "risk" is simply the opportunity cost of missing out on gains above your strike price. The two couldn't be more different.

Stop guessing and start making data-driven decisions. Strike Price gives you real-time probability metrics for every strike, so you can confidently balance safety and income. Turn your portfolio into a consistent income engine today.