Your Guide to the Short Put Position Strategy

If a stock moves past your strike, the option can be assigned — meaning you'll have to sell (in a call) or buy (in a put). Knowing the assignment probability ahead of time is key to managing risk.

Posted by

Related reading

A Trader's Guide to the Poor Man Covered Call

Discover the poor man covered call, a capital-efficient options strategy for generating income. Learn how to set it up, manage it, and avoid common mistakes.

A Trader's Guide to Shorting a Put Option

Discover the strategy of shorting a put option. Our guide explains the mechanics, risks, and rewards of cash-secured vs. naked puts with clear examples.

What Is Risk Adjusted Return? A Practical Guide

What is risk adjusted return? This guide explains how to measure it with the Sharpe Ratio, how to interpret the numbers, and why it's key to smarter investing.

A short put position is an options trading strategy where you essentially act like an insurance company for a stock. In exchange for getting paid cash upfront (the premium), you agree to buy a stock at a set price if it drops. This makes it a bullish to neutral strategy—you profit if the stock price holds steady or climbs.

Thinking Like an Insurance Seller

The best way to get a feel for a short put is to imagine you're an insurance provider for a stock you already like. Let's say another investor owns 100 shares of a company and is worried its price might fall. You can step in and offer them a form of "price insurance."

You agree to buy their shares at a guaranteed price for a limited time. For providing this safety net, you collect an immediate cash payment, known as the premium. This premium is yours to keep, no matter what happens next. It's your reward for taking on the risk.

The Core Parts of the Trade

This "insurance policy" is built on three key pieces that define every short put trade. You'll want to get comfortable with each one before you start.

- The Premium: This is the cash you receive upfront for selling the put option. It also happens to be your maximum possible profit on the trade.

- The Strike Price: This is the specific price you agree to buy the stock at. If the stock’s market price drops below this level by the contract's end, you are obligated to buy 100 shares at this strike price.

- The Expiration Date: This is the date your "insurance policy" runs out. If the stock price is still above your chosen strike price on this date, your obligation is gone. You simply keep the full premium, and the trade is over.

This setup makes a short put a great strategy for anyone who is neutral to bullish on a stock. You don't need the stock to skyrocket; you just need it not to fall below your strike price.

Key Takeaway: Selling a put means you are selling the right for someone else to sell you a stock at the strike price. In return for granting this right, you receive a premium. Your ideal outcome is for this right to go unused.

To pull these concepts together, the table below gives you a quick summary of the short put strategy's main characteristics. We'll dive deeper into how these elements work together throughout this guide.

Short Put Position at a Glance

| Characteristic | Description |

|---|---|

| Market Outlook | Neutral to Bullish. You expect the stock price to stay the same, trade in a range, or increase. |

| Maximum Profit | Limited to the premium collected when you sell the put option. This is your best-case scenario. |

| Maximum Risk | Substantial. Your risk is the strike price (minus the premium received) multiplied by 100 shares. |

| Primary Goal | To generate income from the premium while betting that the underlying stock will not decline significantly. |

This at-a-glance view shows the trade-offs at play: you get immediate income in exchange for taking on the risk of buying the stock if it drops.

Alright, let's move past the "insurance seller" analogy and get into how a short put position actually works on the ground. Understanding the math behind your potential profit, loss, and breakeven point isn't just for show—it’s the core of smart, responsible trading. These three numbers are the foundation of every single put you sell.

The simplest part is your maximum profit. When you sell a put option, the cash premium you collect upfront is the absolute most you can make on that trade. It doesn't matter how high the stock soars; your gain is capped right there at that initial credit.

The Payoff Structure Unpacked

Your main goal? For the option to expire worthless. This lets you keep 100% of the premium you collected, no strings attached. This perfect scenario happens if the stock’s price is at or above your chosen strike price when the expiration date hits. Your obligation to buy the stock just dissolves, and the cash is yours to keep.

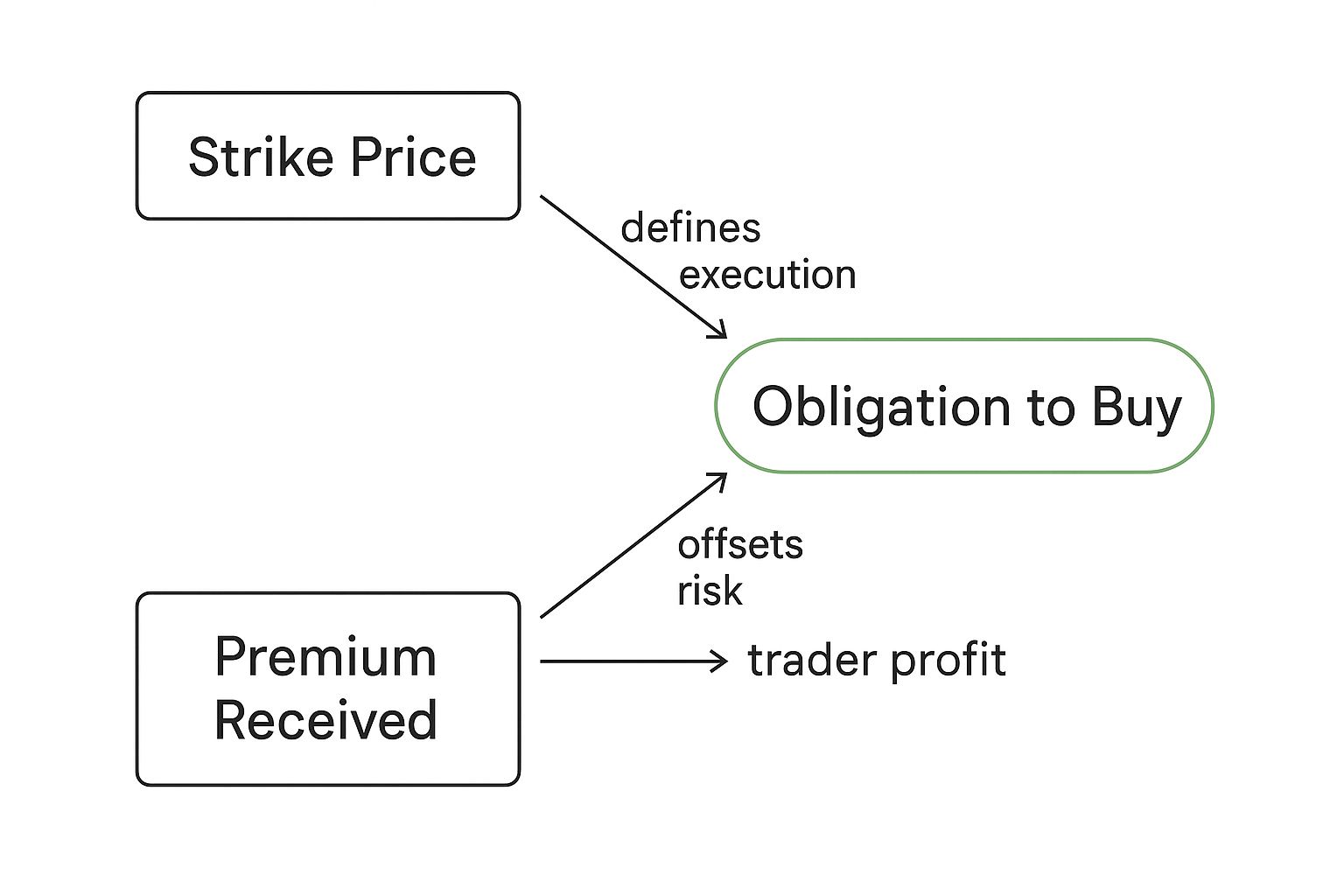

This infographic lays out the moving parts of the trade.

As you can see, the strike price sets up your potential obligation. But the premium you receive does two things: it creates your profit and gives you a small buffer against losses.

So, where's the line in the sand where you start losing money? That's your breakeven point, and the calculation is simple but absolutely critical.

Breakeven Price = Strike Price – Premium Received

This is the price the stock has to stay above for your trade to be profitable (or at least break even). If the stock price dips below this level at expiration, you're looking at a loss. Think of it this way: the premium you pocketed helps offset a bit of the drop, lowering the price where you actually start going into the red.

A Hypothetical Trade Example

Let's make this real. Imagine a stock, we'll call it "Company ABC," is currently trading at $52 per share. You're feeling neutral to bullish on it and figure it's not likely to drop below $50 in the next month. You decide to sell a put option with these specs:

- Strike Price: $50

- Expiration: 30 days

- Premium Received: $1.50 per share ($150 for one contract, which covers 100 shares)

With this info, we can map out the potential outcomes for your short put position.

Maximum Profit: Your max gain is locked in at the $150 premium you collected. You pocket this full amount if ABC closes at or above $50 on expiration day. The option expires worthless, and you're done.

Breakeven Point: We just plug the numbers into our formula: $50 (Strike) - $1.50 (Premium) = $48.50. This is your all-important breakeven price.

Potential Loss: If ABC closes below $48.50, you start losing money. Your loss grows dollar-for-dollar as the stock falls. For instance, if ABC tanks and closes at $45, you're on the hook to buy the shares at $50, even though they're only worth $45. That's a $5 per share loss, but you get to subtract the $1.50 premium you already collected. Your net loss would be $3.50 per share, or $350 on the contract.

This risk-reward dynamic is what the strategy is all about. For another perspective, imagine a European trader sells a put on Company XYZ, trading at €50. They pick a €45 strike price and get a €2 premium. Their maximum profit is capped at €200, and their breakeven is €43 (€45 - €2). But if that stock were to plummet to €30, the loss would be a painful €1,300, showing just how quickly losses can dwarf that initial credit. You can explore a full breakdown of this scenario and see why managing these positions is so important.

Choosing the Right Strike Price and Expiration

Knowing the mechanics of a short put is just the start. The real skill—and where you make your money—comes down to two key decisions: the strike price and the expiration date. These aren't just numbers on a screen; they are the dials you turn to control your risk, your potential profit, and the entire purpose of the trade.

First, you have to know your goal. Are you here to generate steady weekly or monthly income? Or are you trying to buy a great stock at a discount to its current price? Maybe you're just bullish and want to get paid for that belief. Each goal points to a very different strategy.

The Strike Price Trade-Off: Risk vs. Reward

Picking a strike price is all about walking the line between safety and reward. It’s a constant balancing act, and your choice is a direct reflection of how much risk you’re willing to take on. Let's break down the three paths you can take.

Out-of-the-Money (OTM) Puts: This is your conservative play. OTM puts have strike prices below the current stock price, giving you a nice buffer. The stock has to drop a fair bit before you’re at risk of assignment. The trade-off? The premium you collect will be much smaller.

At-the-Money (ATM) Puts: This is a more aggressive move. ATM strike prices are right around where the stock is trading now. You’ll collect a much richer premium, but you have virtually no room for error. A small dip is all it takes to put your put in-the-money.

In-the-Money (ITM) Puts: Less common for pure income plays, but still powerful. ITM puts have strike prices above the current stock price. They offer the highest premiums and are often used by traders who genuinely want to buy the stock. It gives them a very high chance of being assigned shares at the strike, which is a discount to where the stock was when they opened the trade.

So, what’s your take on the market? If you're feeling neutral, a safer, further OTM strike might be your best bet. If you're more bullish, you can creep closer to the money for a bigger payday. For a deeper look, check out our guide on how to choose an option strike price for detailed frameworks.

Leveraging Time Decay and Volatility

Once you've landed on a strike, it's time to pick an expiration date. This decision is all about harnessing the power of time decay, or theta. As an options seller, theta is your best friend. It’s the value an option loses every single day, all else being equal.

As a put seller, you profit from the passage of time. Each day that goes by, the option you sold becomes a little less valuable, pushing you closer to your maximum profit. This decay accelerates dramatically in the final 30-45 days before expiration.

This is exactly why so many income traders sell puts with about a month left on the clock. It's the sweet spot. You get a solid premium upfront and then benefit from that rapid time decay as the expiration date gets closer. Weekly options decay even faster, but they give you less time to be right. Longer-term options decay very slowly and lock up your capital for ages.

Finally, you have to consider implied volatility (IV). When IV is high, the market is expecting big price swings, and that fear inflates option premiums. Selling puts in a high IV environment can be extremely profitable because you're collecting more cash for the same level of risk. But remember, high IV is also a warning sign of uncertainty. It's a classic risk-reward scenario where the potential for bigger gains comes with a need for even closer attention.

Using Data to Improve Your Trading Edge

Successful trading is built on data, not guesses. While a gut feeling might occasionally point you in the right direction, a real, consistent edge comes from understanding the numbers behind your strategy. For a short put position, this means going beyond a simple "I think the stock will go up" and looking at the cold, hard probabilities.

This is where you can turn complex market dynamics into a more predictable numbers game. By digging into the statistical side of selling puts, you can make smarter, more informed decisions that actually line up with your goals and how much risk you're willing to take. The key is knowing which data points matter and how to use them.

Using Delta to Estimate Probability

One of the most practical tools at your fingertips is delta. While it technically measures how much an option's price changes for every $1 move in the stock, it has another incredibly useful purpose. For out-of-the-money options, delta acts as a rough, real-time estimate of the probability that the option will expire in-the-money.

For example, a put option with a delta of 0.20 can be read as having an approximate 20% chance of finishing in-the-money by expiration. Just like that, you can quantify your risk before you even click "buy."

- Low Delta (e.g., 0.10): This signals a lower probability of being assigned the stock, making it a safer position. The trade-off? You'll collect a smaller premium.

- Higher Delta (e.g., 0.40): This suggests a higher chance of assignment, but it rewards you with a larger premium for taking on that extra risk.

This simple check allows you to tailor your short puts to your comfort level. If you want a trade with a high probability of winning, you can pick a low-delta put. If you’re willing to accept more risk for a bigger potential reward, a higher-delta put might be the right fit.

The Win Rate vs. Profitability Trade-Off

A high win rate feels great, but it doesn't always lead to higher profits. This is one of the most important concepts to grasp when selling puts. You have to decide: is your goal to win often, or to win bigger on average? The data shows these two goals often demand very different approaches.

Statistical analysis reveals a clear trade-off between how frequently you win and how much you make per trade. Actively managing for quick, small profits can lead to higher win rates but may underperform a more passive approach over the long run.

For instance, a strategy focused on taking profits quickly—like closing a trade after capturing just 25% of the maximum premium—can hit an impressive win rate, sometimes as high as 98%. But those small wins mean it takes a whole lot of successful trades to absorb the impact of even one big loss.

On the other hand, a more hands-off approach of holding a short put position closer to expiration might have a lower win rate. But historical data on S&P 500 options shows this method can deliver a higher average profit per trade. One comprehensive study analyzing over 41,600 trades found that holding 16-delta puts to expiration yielded a better overall return profile than active profit-taking, despite a lower success rate. To see how different management styles stack up, you can review the full analysis of short put performance data.

The table below breaks down the performance of these two distinct management styles based on historical S&P 500 data.

Short Put Management Style Comparison (S&P 500 Data)

| Management Style | Win Rate | Average P/L per Trade | Best Environment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active Profit-Taking (25% Target) | ~98% | Lower | High volatility, choppy markets |

| Passive Hold-to-Expiration | Lower (~85-90%) | Higher | Low volatility, trending markets |

Ultimately, the "best" approach comes down to your personal trading style and the current market environment. Are you trying to build a consistent stream of small wins, or are you aiming for a higher average profit over time? The data suggests you can't always have both.

A Real-World Short Put Example Using QQQ

Theory is great, but let's walk through a trade to see how a short put position actually plays out. We'll use a popular, highly liquid ETF that tracks the Nasdaq 100: the Invesco QQQ Trust (QQQ). This breakdown will connect all the dots—premium, strike price, breakeven, and the capital needed to make the trade.

Imagine the market scene: QQQ is trading at $475.01. A trader feels neutral to bullish on it, thinking a big drop is unlikely in the near future. They decide to sell a put option to generate some income from that belief.

The Trade Setup

Here are the specifics of the short put they sold:

- Underlying Asset: QQQ (Invesco QQQ Trust)

- Action: Sell 1 Put Contract

- Strike Price: $450

- Premium Collected: $6.73 per share (a total of $673 for the contract)

- Expiration: 44 days

With QQQ at $475.01, the $450 strike price is comfortably out-of-the-money. This gives the trader a nice buffer before the position gets into trouble. The maximum profit is locked in from the start: the $673 premium collected upfront.

The most important number here is the breakeven point. You find it by subtracting the premium from the strike: $450 (Strike) - $6.73 (Premium) = $443.27. For the trade to make money, QQQ just needs to close above $443.27 when the option expires.

Analyzing the Outcome and Capital

This trade is a perfect illustration of how a short put can work, even when markets get a little rocky. Over the next 44 days, QQQ did face some selling pressure but ultimately closed at $460 on expiration day.

Because the closing price was safely above the $450 strike, the option expired worthless. The trader’s job was done. They simply kept the entire $673 premium as pure profit. It’s a classic example of how selling puts can generate income from simple price stability.

A crucial detail here is the capital involved. This was a naked put, which required a margin of $1,973. That's less than a fully cash-secured put, but it's a good reminder that selling options means setting aside capital to cover your potential risk.

While this trade worked out perfectly, the risk was always there. If QQQ had plunged below the $443.27 breakeven price, the position would have started losing money. This case study nails the core trade-off of a short put: you accept a limited, defined profit in exchange for taking on significant downside risk.

For traders looking for another detailed walkthrough, our cash-secured put example offers an excellent side-by-side comparison of a similar strategy but with different capital requirements.

How to Manage Your Short Put Position

Long-term success with a short put position isn’t about being right every time. It’s about what you do when you’re wrong. A stock moving against you isn’t a failure—it's an opportunity to manage the trade and protect your capital.

When a trade sours, you have three primary paths: adjust the position, close it for a loss, or take ownership of the stock. Having a plan for each scenario is what separates a disciplined trader from a gambler.

Adjusting the Trade by Rolling

When a stock drops toward your strike price, your first instinct might be to panic. Instead, consider giving the trade a new lease on life by "rolling" it. This just means closing your current short put and opening a new one with different terms, all in one go.

You can adjust your position in two main ways:

- Roll Out: Close your current put and sell a new one with the same strike price but a later expiration date. This buys you more time for the stock to recover and lets you collect another premium.

- Roll Down and Out: This is the most common defensive move. You close your current put and sell a new one with a lower strike price and a later expiration date. This gives you both more time and more room for error.

The goal with rolling is usually to collect a net credit, meaning the premium from the new put is more than the cost to buy back the old one. This lets you improve your breakeven point while literally getting paid to wait.

Knowing When to Close the Position

Sometimes, the smartest move is to simply admit the trade didn’t work and cut your losses. This means buying back the same put option you sold, which locks in a loss but prevents it from getting any worse.

This is a critical skill. Before you even enter a trade, set a mental stop-loss. For example, you might decide to close the position if the loss hits 1.5x or 2x the original premium you collected. Sticking to a predefined rule like this is how you stop a small, manageable loss from turning into a big one.

Key Insight: A small, calculated loss is just a business expense. An uncontrolled loss that blows up your account is a disaster. Closing a losing trade frees up both capital and mental energy for the next opportunity.

Taking Assignment and The Wheel Strategy

Your third option is to simply do nothing and let yourself be assigned the stock. If your short put finishes in-the-money at expiration, you’ll be obligated to buy 100 shares of the stock at the strike price. If you sold the put on a company you genuinely wanted to own anyway, this is often the ideal outcome.

Once you’re assigned, the trade transforms. You’re no longer an options seller; you're now a stockholder. This immediately opens the door to a new income strategy known as “the wheel,” where you can start selling covered calls against your new shares. Our guide on how to sell covered puts explains how this fits into a larger, cyclical income strategy.

Finally, always practice smart position sizing. No single trade should ever expose you to a loss you can’t easily bounce back from. By spreading your risk across different stocks and expiration dates, you protect your portfolio from one bad trade.

Your Top Questions About Short Puts, Answered

Once you get the hang of selling puts, a few practical questions almost always pop up. Let's walk through the most common ones so you can trade with a clear head.

Cash-Secured vs. Naked Puts

The biggest difference here is collateral. Think of it like a security deposit.

When you sell a cash-secured put, you’re promising to buy a stock at a certain price. To back up that promise, you set aside enough cash in your account to actually buy the 100 shares if you have to. Your risk is completely defined and capped by that cash you’ve set aside (minus the premium you pocketed).

A naked put is different. You sell the put without having the full amount of cash on hand. Instead, you just have to meet your broker's minimum margin requirement. This frees up your capital for other trades, but it comes with a major catch: your risk is technically unlimited until the stock hits zero. A sharp move against you can trigger a margin call, forcing you to close the position at a loss.

When Is the Best Time to Sell a Put?

The sweet spot for selling a put is when implied volatility (IV) is high. High IV means the market is expecting bigger price swings, which inflates the price of options.

You get paid more premium for taking on the exact same level of risk. It’s like selling umbrellas when the forecast calls for a thunderstorm—demand is high, and you can charge a premium.

Key Takeaway: Selling puts when IV is high gives you a statistical edge. You collect a richer premium upfront. If that volatility later cools down (which it often does), the value of the put you sold drops, making it cheaper to buy back for a profit.

What Actually Happens If I Get Assigned?

If your short put is in-the-money when it expires, you’ll be assigned the stock. This just means you have to make good on your end of the deal: you’re obligated to buy 100 shares of the stock (per contract) at the strike price you agreed to.

The cash for the purchase will be taken from your account, and the shares will show up in your portfolio. This isn't always a bad thing! If you wanted to own the stock at that price anyway, assignment is just a way to get it. From there, you could simply hold the shares or start selling covered calls against them—the next step in the popular "wheel strategy."

Clarifying the Maximum Loss

So, can you lose more money than the cash you set aside for a cash-secured put?

Nope. With a properly set-up cash-secured put, your risk is absolutely capped. Your maximum loss is the strike price times 100, minus the premium you already collected. Since you already have this cash sitting in your account, you can't lose more than that amount. Your account will never dip into a negative balance from this specific trade.

Turn your understanding of options into consistent income. Strike Price provides real-time probability data and smart alerts, so you can sell puts with a data-driven edge. Stop guessing and start earning by visiting https://strikeprice.app to see how our members are profiting.